Shane Cotton, interviewed by Kim Meredith

Shane Cotton, Te Puawai, 2020. Installation view: Toi Tū Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist and Michael Lett

The sighting of a waka (canoe) once signalled great fortune or imminent danger was just on the horizon. For leading Aotearoa/New Zealand contemporary artist Shane Cotton (Ngāti Rangi, Ngāti Hine, Te Uri Taniwha) there was never any sign of trouble. Te Puawai, now berthed at the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki as part of Toi Tū Toi Ora, a major exhibition of contemporary Māori art, was originally gifted from his father-in-law. The magnificent handcrafted vessel sat for several years in the artist’s studio, "I thought this is great but I wasn’t quite sure what I was going to do with it," Cotton tells me over a Zoom interview from his home in Russell, discussing the exhibition and his new large-scale mural in downtown Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland Maunga.

Launching onto the art scene in the 1990s, Cotton, who grew up in Upper Hutt, was at the forefront of a renaissance in Māoridom, utilising contemporary methods to challenge the status quo. Lauded over the last several decades, Cotton held major exhibitions at City Gallery Wellington and the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki in the early 2000s before turning 40, followed by the international art world responding eagerly with exhibitions in quick succession in New York and Sydney. His numerous awards include the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship (1998), the Seppelt Contemporary Art Award (1998), a Laureate Award from the Arts Foundation of New Zealand (2008); and a New Zealand Order of Merit for services to the Visual Arts in 2012.

He describes being raised in an average Kiwi family during the '60s and '70s, but Cotton’s sharp and astute demeanour suggests otherwise. Highly articulate, he encourages me to interrupt because he can happily ruminate endlessly about the ideas and underlying themes that have evolved and unfolded in his work over the course of his career. Of course I do no such thing, attempting to capture every single word. “Painting in all forms is my first love,” he declares, the energy of his voice telling that his passion shows no sign of diminishing.

During his years at Ilam School of Fine Arts he quickly realised the significance of the medium: “I knew this was what I was going to do for the rest of my life,” he says. However before the artist could launch, there was one more important maunga (mountain) to climb. “As soon as you leave [art school] you’re looking for subject matter.” The young Cotton started delving into kaupapa Māori, Māori history, and colonial history, before fate tipped its hand; Massey University came calling offering a lectureship in the Māori Visual Arts Programme.

“It was all very new to me.” Cotton was thrown into the deep end during what was a serendipitous and intense period. The juggle was real, studiously learning mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) while simultaneously passing on the knowledge to his students. I ask him to recall those days as a lecturer, what was the experience like? “In some ways, I was in the same situation as my students,” says Cotton. He was teaching several Contemporary Māori Arts history papers ranging across political, social and communal histories, and had the benefit of first-hand narrative from colleagues. “I was working alongside experts in Māori history, learning how important it was to understand history.” He smiled when I joked that he’d found exactly what he’d been looking for—a portal into the world of Te Ao Māori (the Māori worldview).

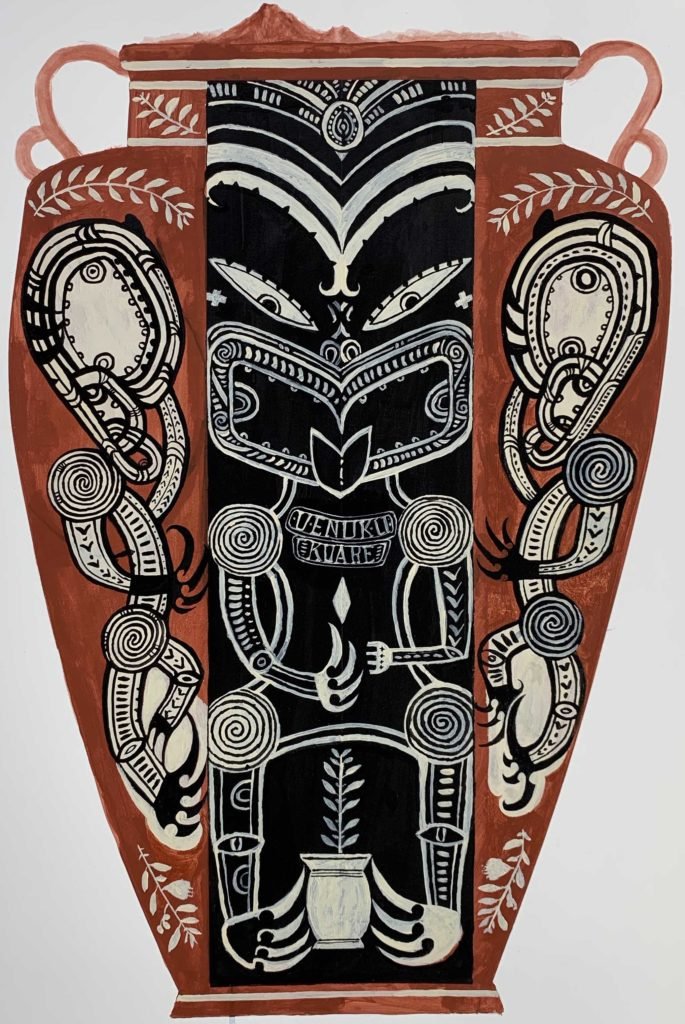

Shane Cotton, Uenuku Kuare, 2020, acrylic on paper. Courtesy of the artist

Shane Cotton, Ruapehu, 2020, acrylic on paper. Courtesy of the artist

This is very likely why vessels, in various forms, have continued to do the heavy lifting in Cotton’s art, performing the essential task of transporting the viewer to places of special connection: people, places and history. The use of Māori motifs, icons, references to the symmetry of Māori carving, landscape and the work of Colin McCahon, both reimagine and confront New Zealand’s history.

The opportunity to co-curate an installation in the Mackelvie Gallery into a space of intervention initially made Cotton apprehensive. Would it work to juxtapose the gallery’s historical collection alongside contemporary Māori artworks? “It took a while to see how it would,” says Cotton in repsonse to being approached by curator Nigel Borrell. “I wasn’t sure about the term ‘intervention.’”

Although Cotton employs the visual medium, he is deeply contemplative about the ideas he brings to the canvas. He tells me that all great things begin by taking the first step, or in the case of the installation, having one piece. Cotton began to envisage how Te Puawai could anchor the installation, how the works around it would be the wake, made buoyant but at little risk of floating away. Venturing into the unknown, Cotton began painting the hull of the vessel, and as the pattern developed, it referenced the journey of places visited, revealing imagery from the past and of special significance, including the kōwhaiwhai pattern of a prominent and sacred whare whakairo (carved meeting house). Te Hau ki Tūranga is the oldest meeting house of its kind, dating back to the 1840s and currently under restoration at Te Papa. Completed by master carver Rukupō with a team of no less than 18 other carvers from Tūranganui-a-Kiwa (Poverty Bay) and Wairoa, it was taken forcibly in 1867 by The Crown, dismantled by government troops and rebuilt at the Colonial Museum—one of the predecessors of Te Papa Tongarewa. Cotton says the iconic whare, with its art, and innovative painting and carving is without equal. How fitting that Te Puawai carries this dark side of history into the well-lit spaces of the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

Cotton shows deftness when he reveals that Maunga, his large-scale mural covering five stories of Excelsior House in downtown Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland, was developed alongside Te Puawai. Although the scope of each project appears vastly different, at its essence, each conveys the same concept—vessels that carry the metaphorical, memories—ideas, history and culture. Maunga, created from a series of 25 works, was commissioned by Britomart for Toi Tu Toi Ora.

The work acknowledges the scale and diversity of Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland. Its painted motifs on the pots of maunga (mountains) draw from the whole of the motu (island), revisiting Cotton’s earlier works in the '90s. Each has a personal relationship for the artist: people; places visited, driven past or dreamt about; and whenua (land) that has made its presence known. He asks if I spotted the pot along the top with the words Fa’a Samoa? Maunga. Indeed it produced its desired effect, I must have resembled a tourist in the city where I was born and raised, pointing upwards with surprise to show my teenage sons, letting out a "choo hoo" at discovering my heritage reflected so prominently. The pot is a connection to an Auckland family with whom Cotton became friends. He speaks fondly but grows solemn about 2020, the toll the Covid-19 pandemic has taken, and the impact of having to live through an existential crisis.

Shane Cotton, Maunga Kiekie, 2020, acrylic on paper. Courtesy of the artist

Shane Cotton, Broken Water, 2003, acrylic on linen. Courtesy of the artist

A journey of an artist whose career has scaled such impressive heights requires leaving no stone, or in Cotton’s case, no vessel unturned. He pauses and says, “they’ve passed on that one,” when I ask how Māori have responded to his depictions of mokomokai (a preserved head with traditional facial tattoo). Although the sacred practice had very specific Māori tikanga (values according to customary practice), mokomokai were part of ritual or a trophy of war. Their trade was borne out of two then incongruous worldviews coming together—Te Ao Māori and Victorian Britain. The British fascination sparked the commodification of mokomokai, which became widespread when the demand for muskets soared.

The image of Major-General Robley from 1895 with his extensive collection of mokomokai, some 35 preserved heads, has been a major reference for Cotton’s exploration. “I’ve approached the use of mokomokai with the possibility of re-working the image. When I started painting earlier images, they were a direct translation.” He talks about the disconnect of body and head, the loss of place. It’s a period of New Zealand’s history that Cotton wasn’t going to overlook. “I wanted to recompose, to project eternal sleep rather than symbols of death.” His later works elevate the mokomokai upwards, placing them in the sky (such as Tradition, History and Incidents, 2007–2009) rather than the earlier translations, “painting allows you to transform imagery.” Cotton transforms mokomokai into abstract vessels that ideas flow in and out of, becoming notions of potential rather than those misfortunate to be caught up in the macabre trade. The artist brings us face-to-face with our dark past, without condemnation, only to reflect and contemplate.

The opening of Toi Tū Toi Ora last December was an assembly of mighty tōtara, contemporary Māori artists who have over the last seven decades made major contributions to capturing cultural shifts in various forms, plumbing the depths and heights of Aotearoa/New Zealand’s history through their work. Cotton is ecstatic when recalling the evening, “to be honest we were all so happy to get together and see one another,” referring to the practice of full-time visual artists often working independently. Watching the next generation was a proud moment, many of Cotton’s former students are now among a cohort of exciting, emerging contemporary artists who continue to break new ground. His response to my final question appears to capture this image. When I ask about the naming of the dinghy, Te Puawai: “It is inspired by the waiata Nga puawai o Ngapuhi that depicts those who flourish today through the exploits of their ancestors.”

Shane Cotton, Tradition, History and Incidents, 2007–2009, acrylic on linen. Courtesy of the artist

Shane Cotton, White Hole, 2017, acrylic on linen. Courtesy of the artist and Nadene Milne Gallery

This text is edited from a version first published in our friend magazine, INDEX, Issue Nº03 (February 2021) — BUY IT HERE NOW.