TAP Book Club: An unreliable guidebook to jewellery by Lisa Walker

“For some strange reason, you have never seen contemporary jewellery. Or been close to it. Don’t blame yourself – it’s a practice so confidential that it flirts with the invisible. It is the bastard child of craft, design and art, and we are still unsure whether it will survive this complicated heritage.”[1]

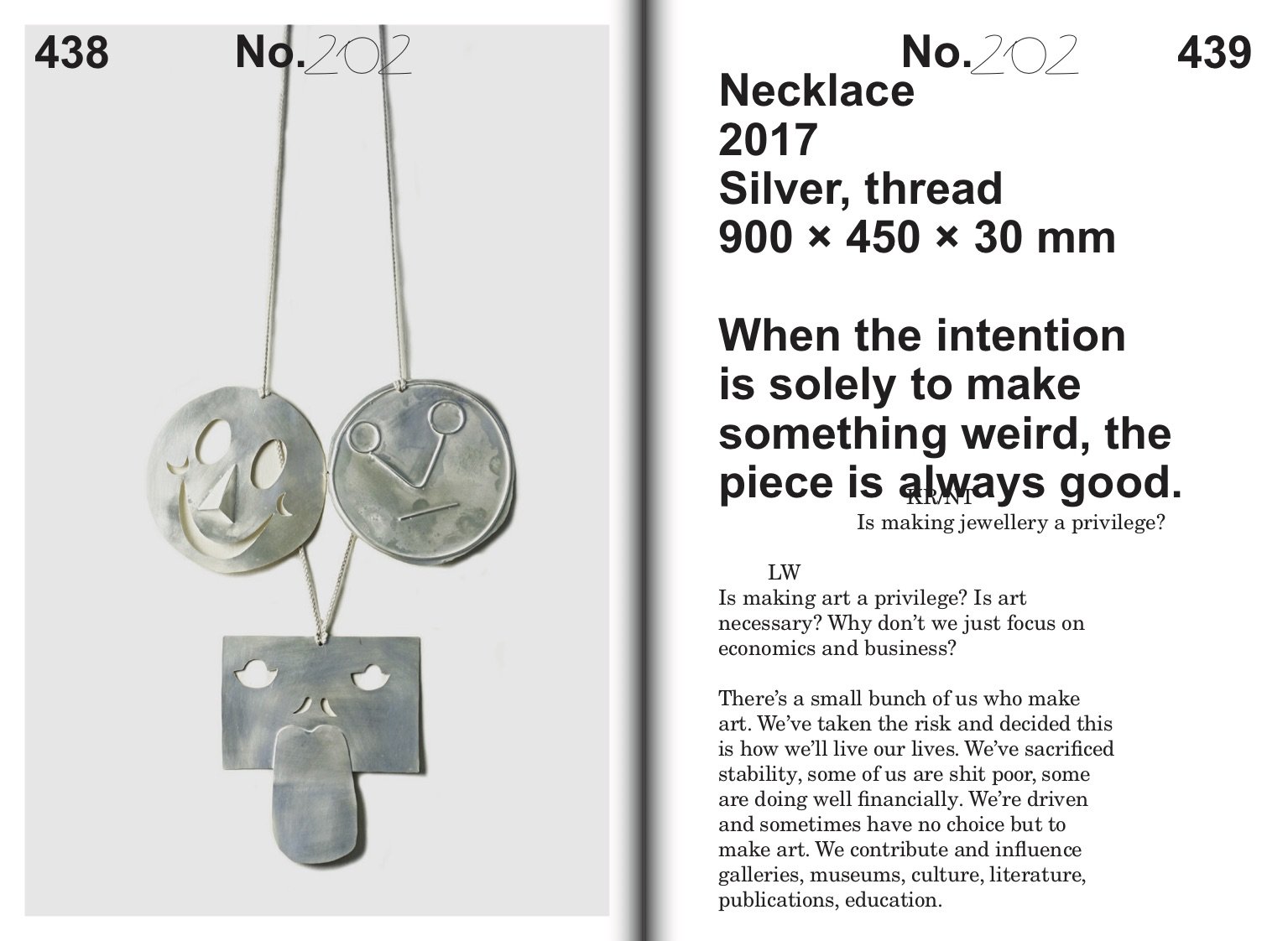

Iconoclastic and irreverent, Lisa Walker is a pioneer of contemporary jewellery. Her pieces defy easy definition. They shift between states, some are wearable, precious, seemingly conventional, while others are made from the debris of Walker’s workshop floor. Some present a puzzle to the viewer: how might you wear it, would you want to? Pieces call to jewellery’s past, speak to current social issues and yet others strive only to be meaningless. Some lurk outside the boundaries of jewellery, defiant and beckoning new meaning.

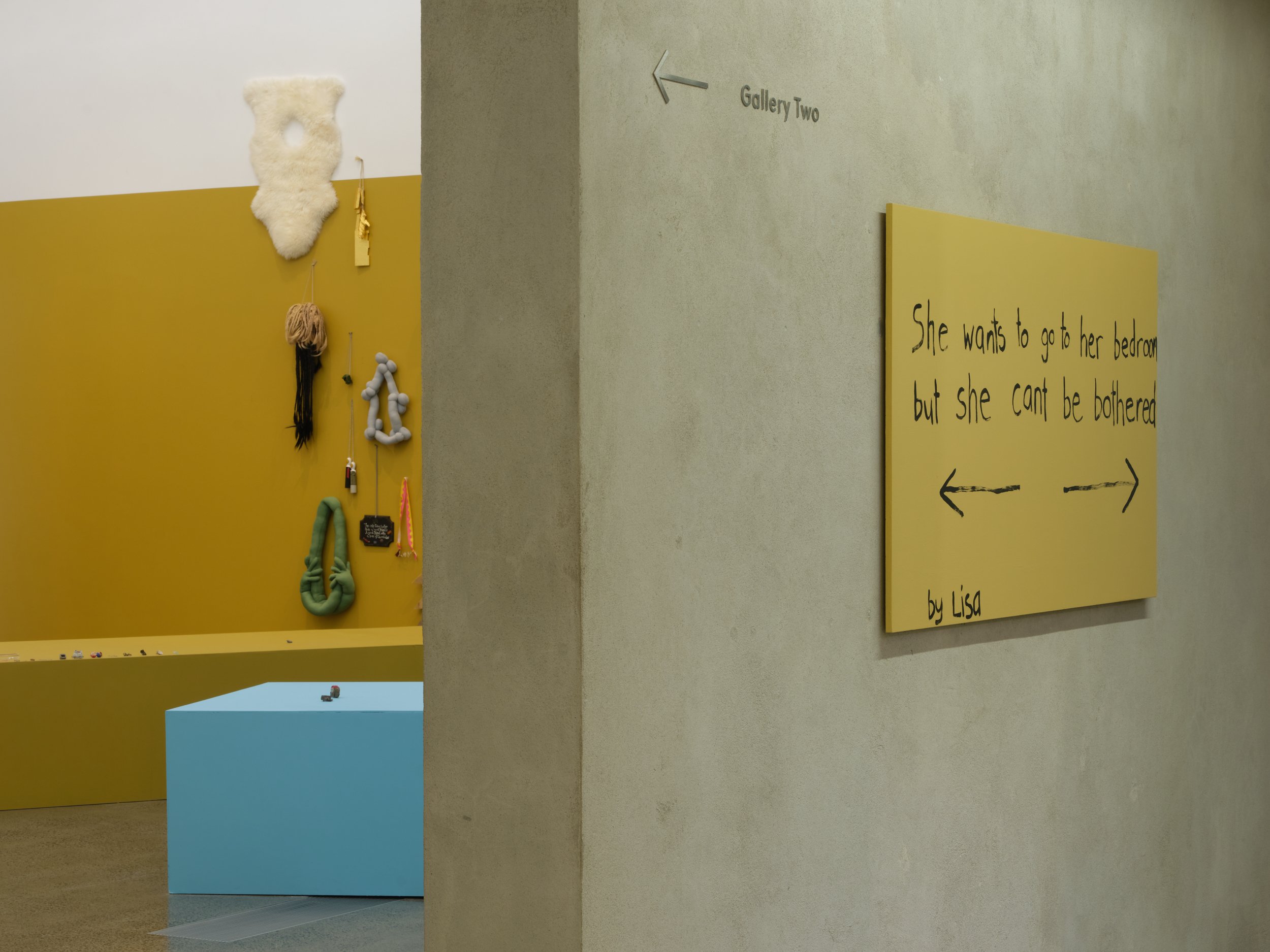

Lisa Walker: She wants to go to her bedroom but she can’t be bothered is a retrospective of Walker’s expansive 30-year career and her exploration of tools, materials and methods for her practice. It contains over 250 pieces, carefully displayed over gallery spaces that each loosely encompass a significant chapter in her career. Initially shown in 2018 at Te Papa, Poneke/Wellington, each subsequent iteration has been added to, re-thought and re-designed by Walker to establish a constantly updated, contemporary presentation.[2] An unreliable guidebook to jewellery by Lisa Walker is a complementary retrospective in written form. Now in its second iteration, it takes on amendments, edits, and mimics Walker’s curatorial and creative practice.

Throughout An unreliable guidebook three texts physically overlap, entering into their respective narrative and typographical space. They are, at times, difficult to read. You can attempt to decipher interlocking serifs that spear memories on barbed tips or move on, knowing you risk a morsel of insight to Walker’s creative practice. The first, begins abruptly in large, bold font:

“1989 I am a student in Dunedin at Otago Polytechnic Art School.”[3]

Excerpt: Lisa Walker; Kate Rhodes and Nell Themelios, eds., An unreliable guidebook to jewellery by Lisa Walker. Melbourne: Perimeter Editions, 2021.

What follows has been written by the artist over thirty years. Lyrical and reflective, it is an accumulation of notes made on scraps of paper and hasty emails to self. It resists temporal isolation, hurling at hyperspeed through a supercut of Walker’s early days: the establishment of Workshop6 in Tāmaki Makaurau alongside jewellers Anna Wallis, Areta Wilkinson and Helen O’Connor. Then, Munich with Professor Otto Künzli, a studio with photographer Eva Jünger, before coming to roost in Pōneke/Wellington.

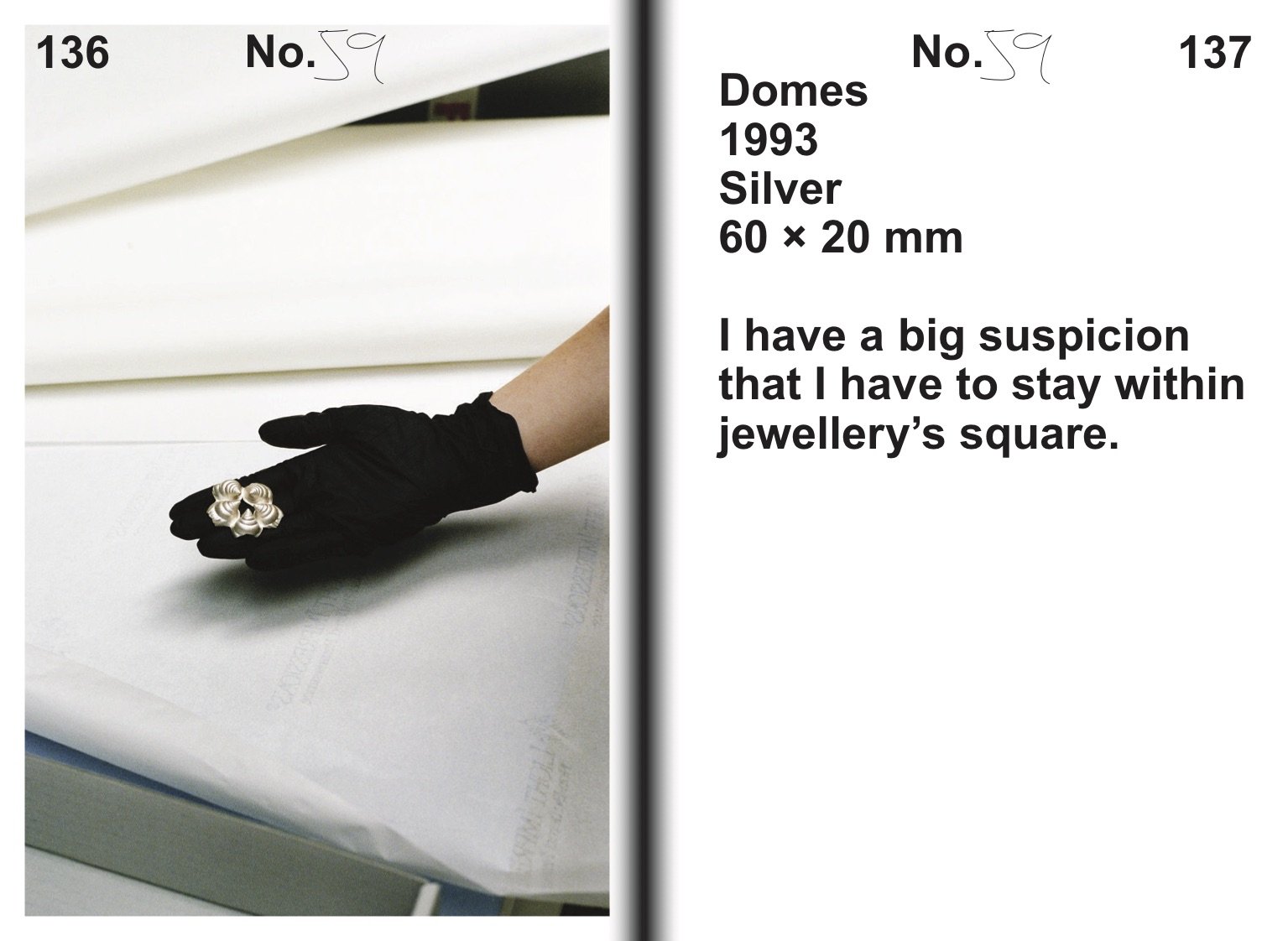

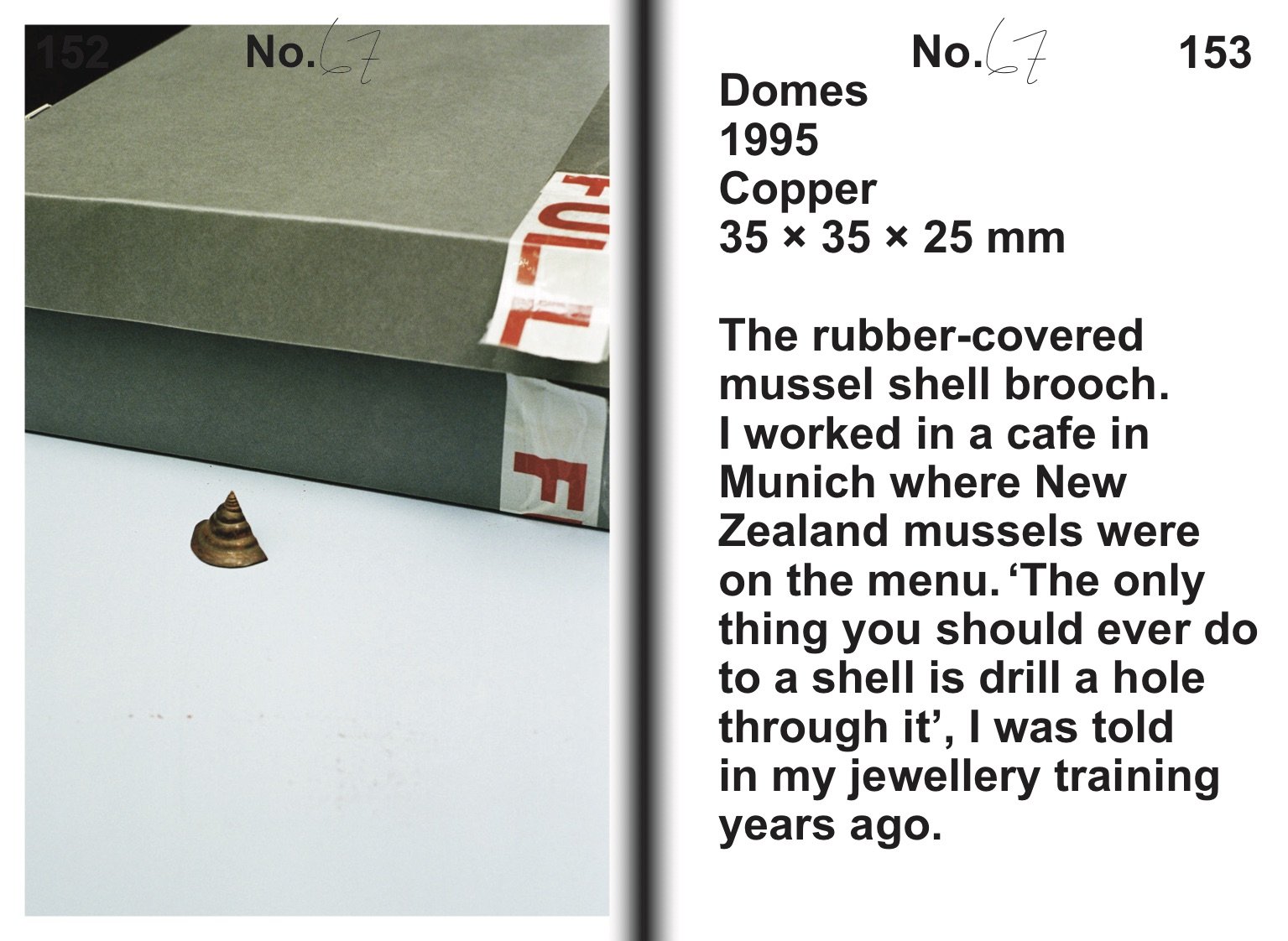

The second text is born of questions posed by editors Kate Rhodes and Nella Themelios. The third is Walker’s responses to their questions, wherein she frequently dips into the words of the first text—she too is transported back to the point of writing, indulging in her thinking and work relevant to those individual passages. She’s surprised by how that text remains relevant at the time of the interview.

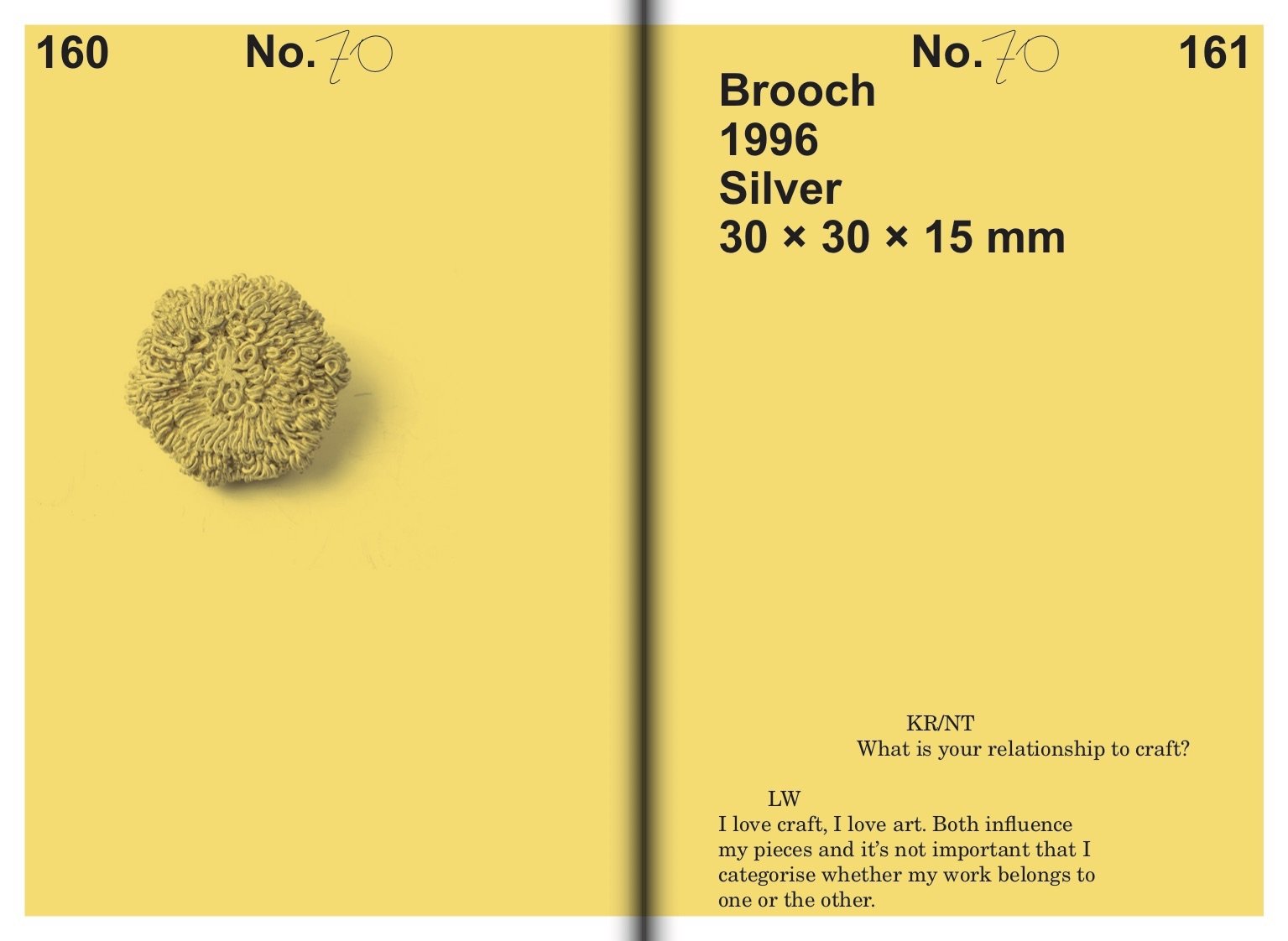

Walker is an unreliable guide, exerting a puckish humour as she answers with deep insights, or slyly side-steps the editor's questions. It is worth considering the ongoing use of the term ‘jewellery’ in lieu of the “meta category of wearable objects,” ‘adornment’.[5] The latter acknowledges a breadth of cultural production that the former excludes. ‘Jewellery’ is born out of medieval Europe, constructed of metal and precious stone, preserved with the honesty of goldsmithing. It’s a kind of high-art that denotes the other: ‘low-art’ that gestures to something outside these parameters—something liminal and organic—craft. Walker notes, “I love craft, I love art. Both influence my pieces and it’s not important that I categorise whether my work belongs to one or the other”.[6]

Excerpt: Lisa Walker; Kate Rhodes and Nell Themelios, eds., An unreliable guidebook to jewellery by Lisa Walker. Melbourne: Perimeter Editions, 2021. Photograph by Layla Cluer.

Contemporary jewellers or artists working with adornment wrest with this legacy, responding to and subverting its emphasis on materials and place. Consider, Sione Tuívailala Monū and their ongoing exploration of nimamea’a tuikakala, the Tongan fine art of flower design using the form of kahoa or Tongan garland. On display as part of The Inner Lives of Islands at Te Tuhi, Monū’s sculptural clouds in ‘Ao kakalaare reference generational knowledge and traditional practices that are re-presented via contemporary means. Nimamea’a tuikakala rendered in plastic flowers and beads, gathered from the bountiful garden of South Auckland variety stores, stocked by giant Chinese online retailers.[7] Monū plays with the associations we have, and those we project on materials.

Walker too explores materials from increasingly diverse sources—see numerous references to trying to make jewellery with “beach materials” but not wanting to make anything “beach hippie” (87), her love for the goldsmith’s cheat, glue (163); and eventually, debris taken from the floor of her workshop. Plenty of her works are readymades—pre-produced, everyday objects that are transposed into an art environment and anointed divine, conceptual meaning. Walker takes inspiration from culture and everyday life and transplants the familiar— be it stuffed toys or the Simpsons—staging them as jewellery, hijacking and reformulating their meanings. Her work defies the craft/art distinction, pulling taught the tensions between old and new, beauty and strangeness.

Excerpt: Lisa Walker; Kate Rhodes and Nell Themelios, eds., An unreliable guidebook to jewellery by Lisa Walker. Melbourne: Perimeter Editions, 2021. Photograph by Layla Cluer.

Walker engages with photography as part of her practice by documenting each and every piece. In the past, she would model her own works out of convenience. An unreliable guidebook highlights the natural intersection between making jewellery or adornment and photography, wherein Walker cites the natural desire of jewellers to see people wearing their work. She notes how pieces become part of the wearer, fusing with them, transmuting. Walker has long documented her jewellery practice, photographing each piece against a white or grey background. She admits to hoarding materials now inclusive of digital imagery saved on social media or an Etsy wishlist. Although she maintains that these are just a personal archive, I can’t help but see how the images of her work in the guidebook reference this utilitarian approach.

The documentation of her work in the guidebook doesn’t always align with the text, sometimes suggesting a gap in time, an interrupted thought. Some aspects of practice exceed words. In the foreword to An unreliable guidebook to jewellery, the editors explain that the physical overlapping of text emphasises intertextuality. They acknowledge that a retrospective can often feel like “a totalising answer to the question ‘what has this all been about?’” In response, they posit questioning as the heart of this book. What is yet to be known should be relished and enjoyed. The book, in part, is a response to the exhibition; but both are an ongoing investigation into the nature of creative practice. Both support the unknown which hangs comfortably in the air around you. You feel safe to ask, ‘what actually is contemporary jewellery?’ and to feel at ease not knowing the answer.

Footnotes:

[1] A quote from the exhibition Collect Rocks, Plant Flags (2011) curated by Leo Caballeo and Amador Bertomeu with the support of Benjamin Lignel. In Walker, Lisa, Kate Rhodes and Nell Themelios, eds., An unreliable guidebook to jewellery by Lisa Walker, (Melbourne: Perimeter Editions, 2021), 391.

[2] Lisa Walker: She wants to go to her bedroom but she can’t be bothered travelled to RMIT Design Hub in Australia, Museum Villa Stuck in Germany and CODA Museum in The Netherlands, before coming to roost at Te Uru this year.

[3] Walker, Rhodes and Themelios, An unreliable guidebook to jewellery by Lisa Walker, 9.

[4] Ibid, 10.

[5] De Gruijter, Vanessa, "Decolonise Contemporary Jewellery," Current Obsession, March 22, 2020.

[6] Walker,Rhodes and Themelios, An unreliable guidebook to jewellery by Lisa Walker, 161.

[7] Robbie Handcock, curatorial statement for The Inner Lives of Islands, Te Tuhi, 30 May–22 August 2021.

[8] First at Fresh Ōtara Gallery (2017) and later at Objectspace (2018).

Excerpt: Lisa Walker; Kate Rhodes and Nell Themelios, eds., An unreliable guidebook to jewellery by Lisa Walker. Melbourne: Perimeter Editions, 2021.

Excerpt: Lisa Walker; Kate Rhodes and Nell Themelios, eds., An unreliable guidebook to jewellery by Lisa Walker. Melbourne: Perimeter Editions, 2021.

Excerpt: Lisa Walker; Kate Rhodes and Nell Themelios, eds., An unreliable guidebook to jewellery by Lisa Walker. Melbourne: Perimeter Editions, 2021.

Excerpt: Lisa Walker; Kate Rhodes and Nell Themelios, eds., An unreliable guidebook to jewellery by Lisa Walker. Melbourne: Perimeter Editions, 2021.

Lisa Walker, Lisa Walker: She wants to go to her bedroom but she can't be bothered. Installation view, Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery, 5 June 2021. Photograph by Sam Hartnett.

Lisa Walker, Lisa Walker: She wants to go to her bedroom but she can't be bothered. Installation view, Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery, June 2021. Photograph by Sam Hartnett.

Lisa Walker, Lisa Walker: She wants to go to her bedroom but she can't be bothered. Installation view, Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery, June 2021. Photograph by Sam Hartnett.

An unreliable guidebook to jewellery by Lisa Walker, edited by Kate Rhodes and Nella Themelios was originally published in 2019 to accompany Lisa Walker: She wants to go to her bedroom but she can’t be bothered while on display at RMIT Design Hub Gallery, Melbourne, Australia. A new edition has since been published with support from Creative New Zealand to coincide with the final iteration of the exhibition, on view at Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery, 5 June–29 August 2021, Aotearoa/New Zealand. The book was designed by Ziga Testen Studio, Melbourne.

Lachlan Taylor on Barbara Tuck’s painting Dipping Mortal (2014)—republished from an exquisite collection of essays in the new book Delirium Crossing, edited by Anna Miles and Christina Barton.