Rumpus (Room)

Kirsty Lillico speaks to Hannah Mahon about her recent installation with Yu Mei.

Kirsty Lillico, Nose to tail (pink) (detail), 2022, deer nappa offcuts, foam, pine dowel, plywood, 66 x 59 x 13 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Hannah Mahon

Kirsty Lillico styled by Jess Scott — wearing Burnished Jewellery earrings, Nike winged top (reworked), and Depth of Scye skirt; all from Bizarre Bazaar. Photographed in the Yu Mei showroom by Hannah Mahon, April 2022. Courtesy of The Art Paper

Hannah Mahon: Let's begin by speaking about your recent presentation at Yu Mei in Wellington, Rumpus. How did the collaboration come about?

Kirsty Lillico: I was approached by Jhana Millers, one of the organisers of the Threads Textiles Festival in Te Whanganui- a-Tara Wellington. As part of the programme, a handful of artists were paired with local fashion businesses to make use of textile waste by producing an exhibition for their retail store.

I visited Yu Mei’s workshop and they gave me some samples, which included deer nappa, calf skin, and also some hardware—things like chains, and canvas strapping. Like carpet, a material I often use, leather is a non-fraying, (reasonably) robust material with strong sculptural potential. I was seduced; after my previous project where I was working with scratchy dusty carpet, the leather felt so smooth and soft. But I also had some reservations…

Because you don’t eat animal products, right?

Yes, I was very uncertain about doing this project at all. I reasoned that I was going to be using offcuts (a waste product) of a material that Yu Mei describes as being a by-product itself (from the venison industry). But I still felt that the death of an animal could be aestheticised or celebrated through my making the artwork. Instead, I wondered if I could acknowledge the deer in some way; and tried using the leather to stretch over a structure that might recall the bones and cartilage of an animal.

If a body is evoked in the final artwork though, it’s probably the (female) human body. My thinking is influenced by vegan feminism. I believe that the objectification and exploitation of animals’ lives and bodies is a feminist issue, because feminism is all about fighting against the way the patriarchy privileges one group’s interests and subjectivity over another. Speciesism and sexism are socially constructed hierarchies that objectify (animal’s and women’s) bodies in order to dominate and control.

Was there a sense of disruption or disturbance in the way you envisaged these artworks would sit in the space, as indicated by the name, Rumpus?

Not physically—the work sits on the wall in a polite well-behaved row, somewhat like the shelves of handbags in the shop.

The title references a rumpus room—I was thinking about a space that’s the antithesis of a luxury goods retail store. I’ve combined the leather with cheap materials like plywood and yellowing foam, the kind of materials you might find in a basement, garage or sleepout. In doing so, I was aiming to ‘de-luxurify’ the material and the shop. This is also the reason I chose to use stapling, rather than sewing. I didn’t want to use any craft technique that was going to elevate the leather through the application of skill. Instead, I wanted to interrupt the semiotics of these luxury goods, and question the power of commodity fetishism.

You often incorporate offcuts into your practice. Past exhibitions such as Unravelled (2019) used end-of-roll carpets. Did your process differ, working directly with Yu Mei and using materials that were provided rather than sourced by you?

By incorporating found materials, I am employing chance as a strategy, to function either as a limitation or a starting point. I often like the discarded pieces that end up on the floor better than the thing I am making.

I decided to avoid altering the shapes of the offcuts, partly because I didn’t want to make more waste. The natural shape of the leather the outer edge formed the outer edge of each sculpture, and therefore determined the overall shape of each sculpture. The various colours of the offcuts represented four years of Yu Mei’s production—how many fashion cycles is that? When we think about fashion, we think about ‘trends’ and a system that’s based on constant change. Whereas the cliché is that art aims for timelessness.

You've spoken before about the art historical links in your practice, and the connection to modernism. Can you extrapolate how these ideas come to the fore in your latest body of work?

This project connects to modernism not as an artistic style but, in broader sense, to industrial production and pre-consumer waste.

In terms of art references, I thought about other artworks that hang on the wall but act more like sculpture than painting. Alberto Burri and Lucio Fontana both made work in this category. Their canvases, pierced by cuts and punctures, function as metaphors for the body. Also of relevance—the post-minimalist sculpture of Eva Hesse and Robert Morris, who both used industrial textiles to create biomorphic abstract form. The vulva imagery of Judy Chicago and Magdalena Abakanowicz.

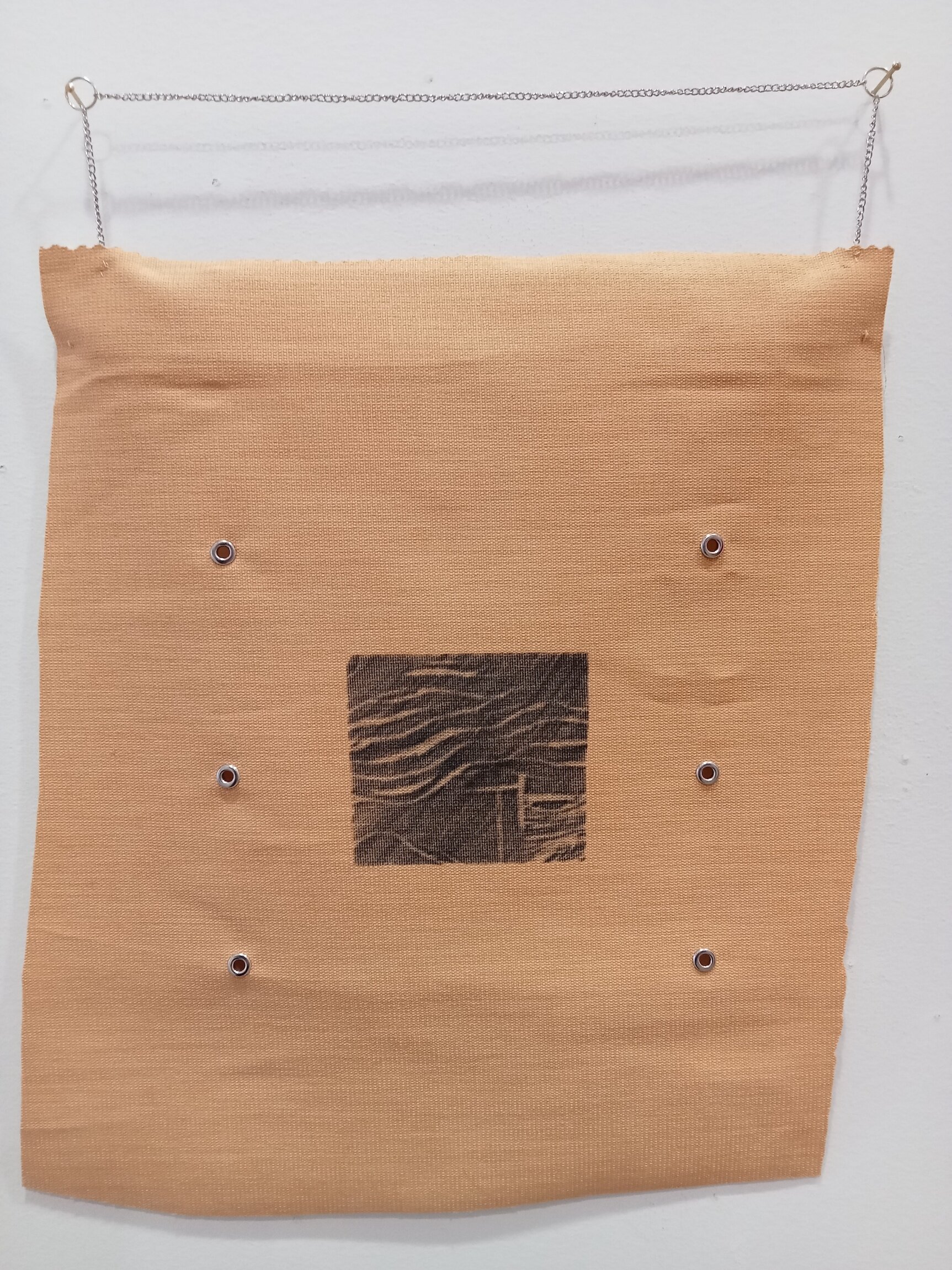

Kirsty Lillico, Don’t bite me (yellow), 2022, deer nappa offcuts, foam, plywood, 80 x 62 x 18 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Hannah Mahon

Kirsty Lillico, Love Operation (blue), 2022, deer nappa offcuts, foam, plywood, 71 x 61 x 8 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Hannah Mahon

Kirsty Lillico, Nose to tail (pink), 2022, deer nappa offcuts, foam, pine dowel, plywood, 66 x 59 x 13 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Hannah Mahon

Kirsty Lillico, Don’t bite me (yellow) (detail), 2022, deer nappa offcuts, foam, plywood, 80 x 62 x 18 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Hannah Mahon

Kirsty Lillico, Love Operation (blue) (detail), 2022, deer nappa offcuts, foam, plywood, 71 x 61 x 8 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Hannah Mahon

Kirsty Lillico styled by Jess Scott — wearing Burnished Jewellery earrings, Broken Studios corset, and acid2513 jacket; all from Bizarre Bazaar. Photographed in the Yu Mei showroom by Hannah Mahon, April 2022. Courtesy of The Art Paper

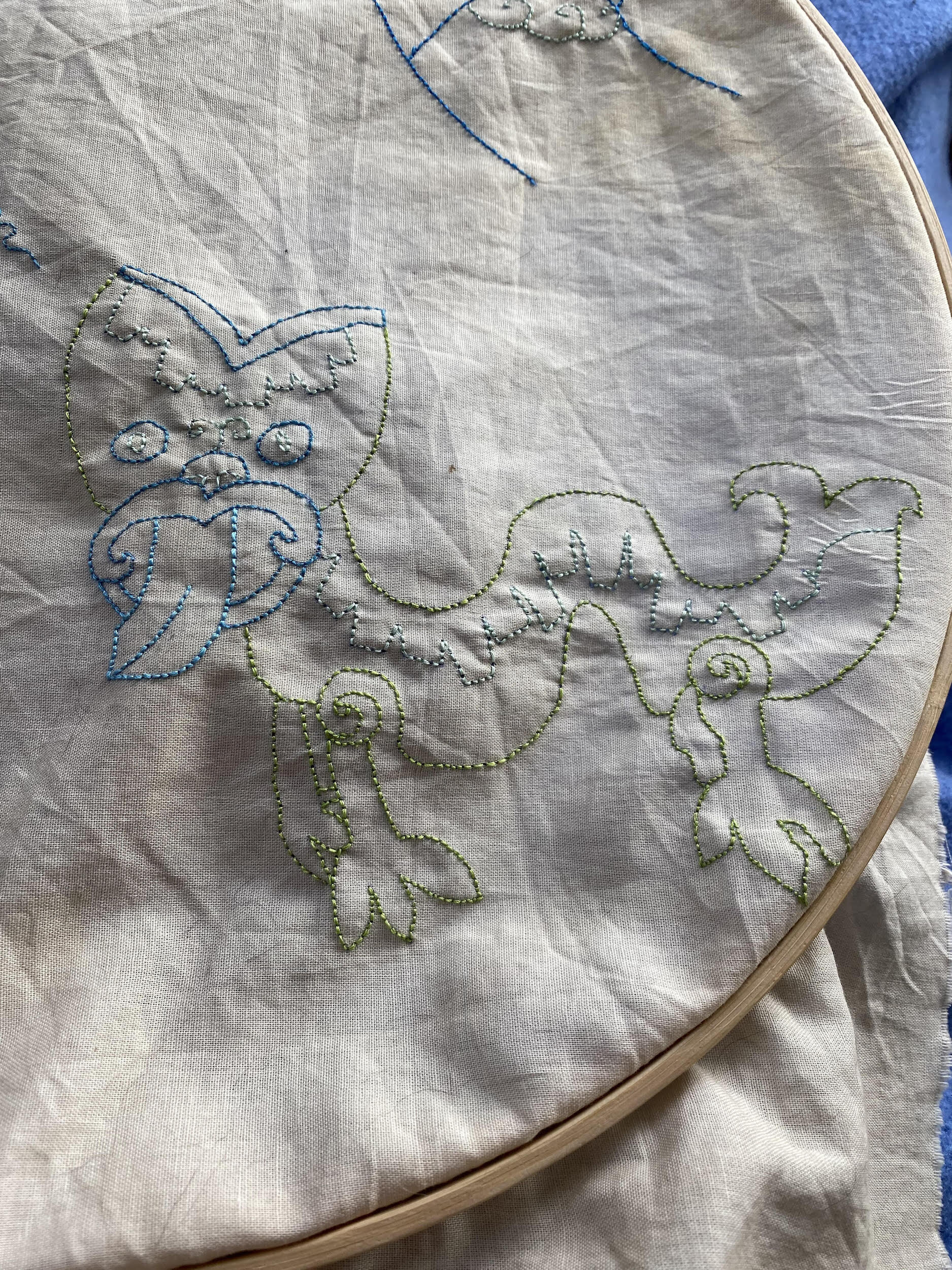

Hannah Crichton speaks to Polly Gilroy about her recent exhibition, Traces.