On Returning: Hamish Coleman and Emily Hartley-Skudder in conversation

Equal parts portrait of the land and of himself, Hamish Coleman has captured and cropped still images from his own videos taken while revisiting particular locations from his childhood. Rendering these in iridescent oil paint, he alludes to an unsettling sense of nostalgia centred on people and places; on remembering and forgetting.(1)

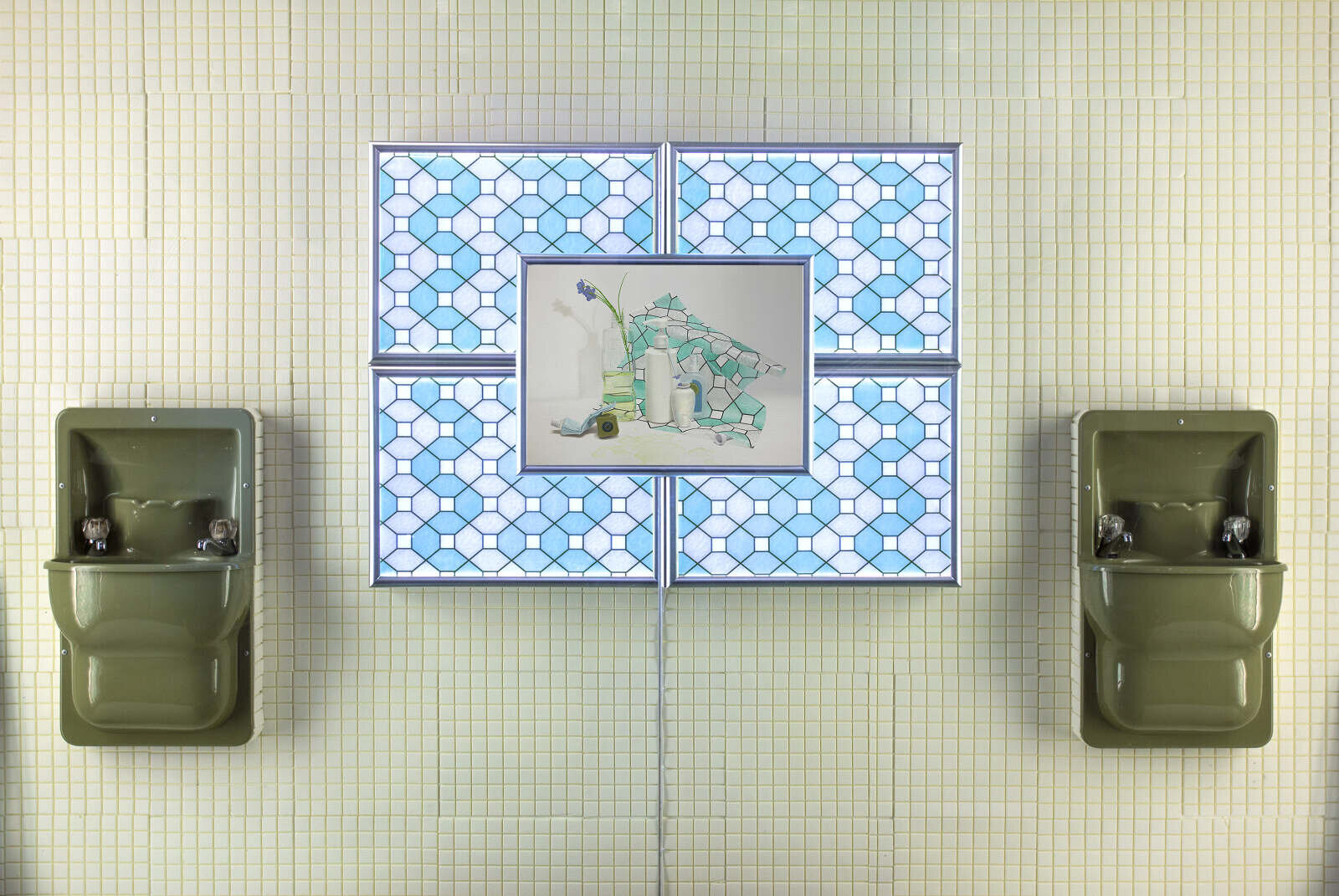

Hamish Coleman, On Returning. Installation view, Ashburton Art Gallery, Hakatere, April 2021. Courtesy of Bartley & Company Art. Photo: Emily Hartley-Skudder

Emily Hartley-Skudder: Ashburton is a small town south of Christchurch that people in Aotearoa/New Zealand seem to love to trash talk. When we were friends during our time at Ilam [School of Fine Arts, Canterbury], I’d always send you a one word text: ‘ASHVEGAS!’ when driving through on a road trip. What do you think it is about Ashburton?

Hamish Coleman: Yes, I remember the text messages. For the population that lives outside of Ashburton, it’s more often a place to pass through and less of a destination in it’s own right.

‘Vegas’ seems to be a tail that’s tacked on the end of many small towns throughout Aotearoa, and like ‘Dannevegas’ or ‘Rotovegas,’ ‘Ashvegas’ is a small town that’s just big enough to be poked at for its lack of excitement. I suppose it’s a rural service town that values function over form, rugby over painting, and inherently, it’s not necessarily a place where you’d think of the arts flourishing. But it’s where I come from.

You are a self-described ‘painter’s painter;’ people may have heard how you hand-mull iridescent pigment with oil to make your own paint, and paint on coarse Belgian linen that you stretch yourself. Can you speak a little about your other interests that run tangentially to and feed into your practice?

Every art form needs its own supporters and patrons, and I’m quite into music. I always listen to music in the studio when I paint, it helps me get into a good place for it. When I’m listening, I’m also taking notes, writing down song titles and lyrics as I go, eventually using them as ideas for titles of paintings. For a good few years I absolutely wrung the heck out of Wire’s first three albums in the studio. People familiar with those songs could go through my back catalogue of work and spot the references.

I always see a good exhibition like a good album—variation, highs and lows, quiet and loud. Talking about something personal, but anyone listening can impart their own narrative or histories upon it. The keen viewer will soak up the artwork like a sponge if it’s successfully operating as more than just a picture.

We visit Ashburton a couple of times a year to see your mum, but you never want to stay too long. Over the past several years, this has become a kind of reluctant pilgrimage to get source material for your paintings. It’s a bit like a treasure hunt for me—we drive around the long, straight roads, seeking out significant places you remember from growing up, to film with a point-and-shoot camera. It seems like a way for me to get to know you better, as you re-discover and process things from your childhood. Can you talk about this approach, and how parts of this unrehearsed, candid footage end up as final paintings?

It’s a complicated relationship that I have with going home. There’s comfort, but it’s also apparent that I’m not able to assimilate back into an earlier part of my life. I think that’s a fairly common attitude for others when visiting their hometowns.

Over the past few years working on this project, I’ve surprisingly found it very cathartic. During this period also I’ve reconnected with my father for the first time in 17 years. I think it’s worth adding that I had absolutely no idea what to expect when I set out with my list of places and my camera. It’s been special sharing this strangely restorative process with you, Emily. You appear in three of the paintings in my exhibition. Old places with current faces.

With regards to my process—I re-watch my footage and take screen captures, then crop these down further. There’s a certain thrill in capturing a split-second image from a film and spending weeks or months rendering it in paint. I call these screen captures ‘non-images’, and they are what I’m searching for. It’s as if the figure, land and trees were caught off guard, or as if I were a second too slow in capturing a posed scene found through a conventional photograph.

I think it’s significant to mention the content of your earlier work, which makes the shift to autobiographical subject matter all the more pointed. The other day we watched White Riot (2019), the documentary about the British organisation Rock Against Racism in the ‘70s, and you recognised a piece of historical footage that you had made into a painting years ago at art school. What was it about this kind of subculture that fascinated you, and do you think it was something you had to get out of your system before looking inwards?

That scene with Joe Strummer on stage was instantly recognisable to me. Eleven years ago I went through YouTube and took a still from a low-quality 280p video and made it into a painting. I used found footage in part because I was wanting to be cool and distant, like one does during art school, but also it meant the focus wasn't on me in that imagery.

Until about four years ago I was making paintings from YouTube, and then I began using scenes from Aotearoa/New Zealand short films and music videos to make an obtuse, heavily cloaked narrative. Something clicked, and perhaps it was me fast approaching thirty, but I felt it was time to make paintings that had personal reference. It was actually you, Emily, that encouraged me to try making my own films for source imagery. It wasn’t a process that happened overnight. I found it awkward looking inwardly, but deeply rewarding.

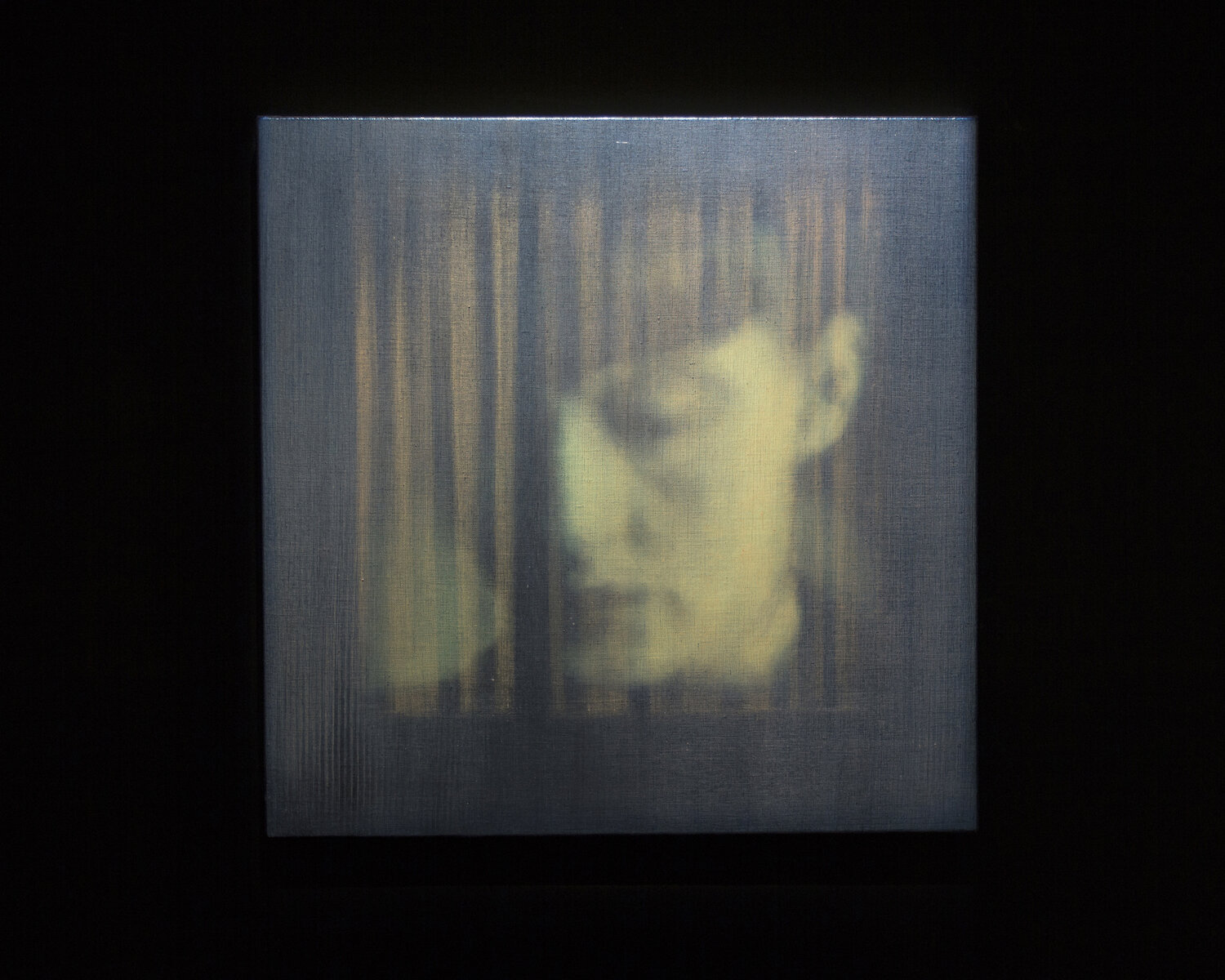

As you’ve mentioned, I appear in some of the paintings. Your brother does too. We’ve joked about how the work depicting a close-up of my face, titled Dear, makes me look like a ghost. What was it like painting people close to you, compared to the anonymous faces you used to paint? Can you touch on the darkness that underpins these works?

Well, I’ve painted many anonymous faces over the years, and also you and my brother. It just feels right painting someone dear to you, like, there’s a likeness to that particular character that is very important to achieve in paint. Dear is such an odd work because it’s really solemn and cold looking. It’s perhaps more indicative of your more depressive side, Em. But the sincerity to the subject remains, and I laboured over that painting, probably more than anything else in that exhibition. It had to be right.

I also think the material qualities of my paintings are reflective of the emotional tones I’m trying to bring to the fore. I want the paint to carry its share of the load. Otherwise I’d just present the stills as printed images.

The dreaded final question: what’s next?

Ugh, don’t ask me that. I tend to work progressively and organically, each work builds upon the previous one, rather than focussing on individual projects. I sometimes re-visit footage and can discover a whole new series of stills. The videos have stayed the same, but how I look at them has changed with time.

Footnotes

(1) Ashburton Art Gallery, "On Returning: About this Exhibition," April 2021 (accessed 2 May 2021).

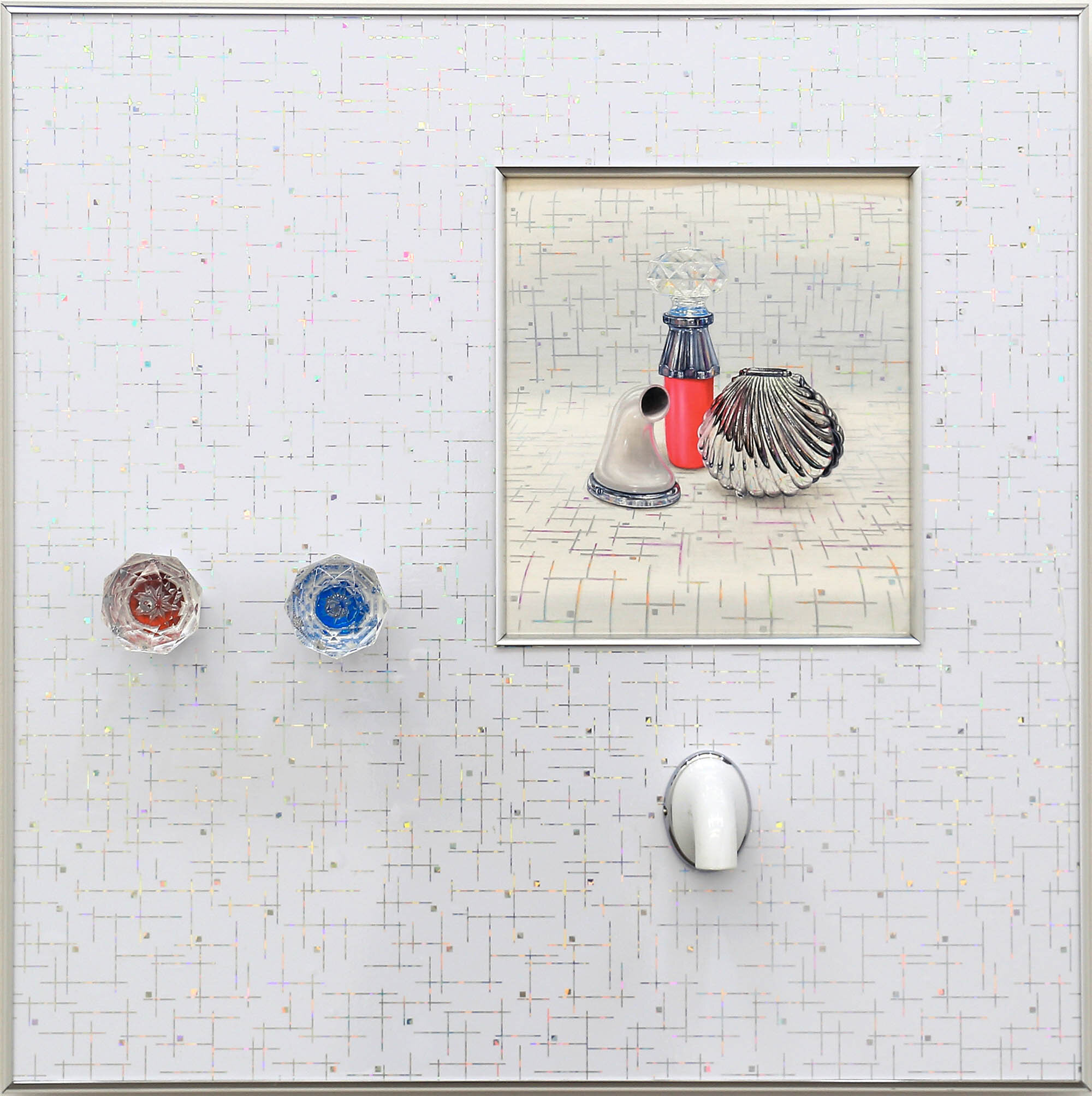

Hamish Coleman, Glint, 2020, oil on linen, 182.5 x 182.5 cm. Courtesy of Bartley & Company Art. Photo: Emily Hartley-Skudder

“I also think the material qualities of my paintings are reflective of the emotional tones I’m trying to bring to the fore. I want the paint to carry its share of the load. Otherwise I’d just present the stills as printed images.”

Hamish Coleman, On Returning. Installation view, Ashburton Art Gallery, Hakatere, April 2021. Courtesy of Bartley & Company Art. Photo: Emily Hartley-Skudder

Hamish Coleman, Dear, 2019, oil on linen, 71.5 x 71.5 cm. Courtesy of Bartley & Company Art. Photo: Emily Hartley-Skudder

Hamish Coleman, Places Creep, 2021 oil on linen, 137 x 137 cm. Courtesy of Bartley & Company Art. Photo: Emily Hartley-Skudder

Hamish Coleman, On Returning. Installation view, Ashburton Art Gallery, Hakatere, April 2021. Courtesy of Bartley & Company Art. Photo: Emily Hartley-Skudder

Hamish Coleman, On Returning (diptych), 2019, oil on linen, 140.5 x 240 cm overall. Courtesy of Bartley & Company Art. Photo: Emily Hartley-Skudder

Hamish Coleman, Reclamation, 2021, oil on linen, 30.5 x 30.5 cm. Courtesy of Bartley & Company Art. Photo: Emily Hartley-Skudder

Hamish Coleman, A Quiet Man, 2020, 60.5 x 60.5 cm. Courtesy of Bartley & Company Art. Photo: Emily Hartley-Skudder

Hamish Coleman, Glint (detail), 2020, oil on linen, 182.5 x 182.5 cm. Courtesy of Bartley & Company Art. Photo: Emily Hartley-Skudder

Hamish Coleman, Friend Catcher, 2020–21, oil on linen, 182.5 x 182.5 cm. Courtesy of Bartley & Company Art. Photo: Emily Hartley-Skudder

Hamish Coleman, On Returning. Installation view, Ashburton Art Gallery, Hakatere, April 2021. Courtesy of Bartley & Company Art. Photo: Emily Hartley-Skudder

On Returning is on view until 16 May at Ashburton Art Gallery, Aotearoa/New Zealand. It will then make its way to Te Whanganui-a-Tara/Wellington to be shown at Bartley & Company Art, opening 8 May 2021.

Francis McWhannell on Hamish Coleman, Wax and Wane, 13 May–17 June 2023.