Rea Burton, on friends and pests

Rea Burton, Mates. Installation view, Robert Heald, March 2021

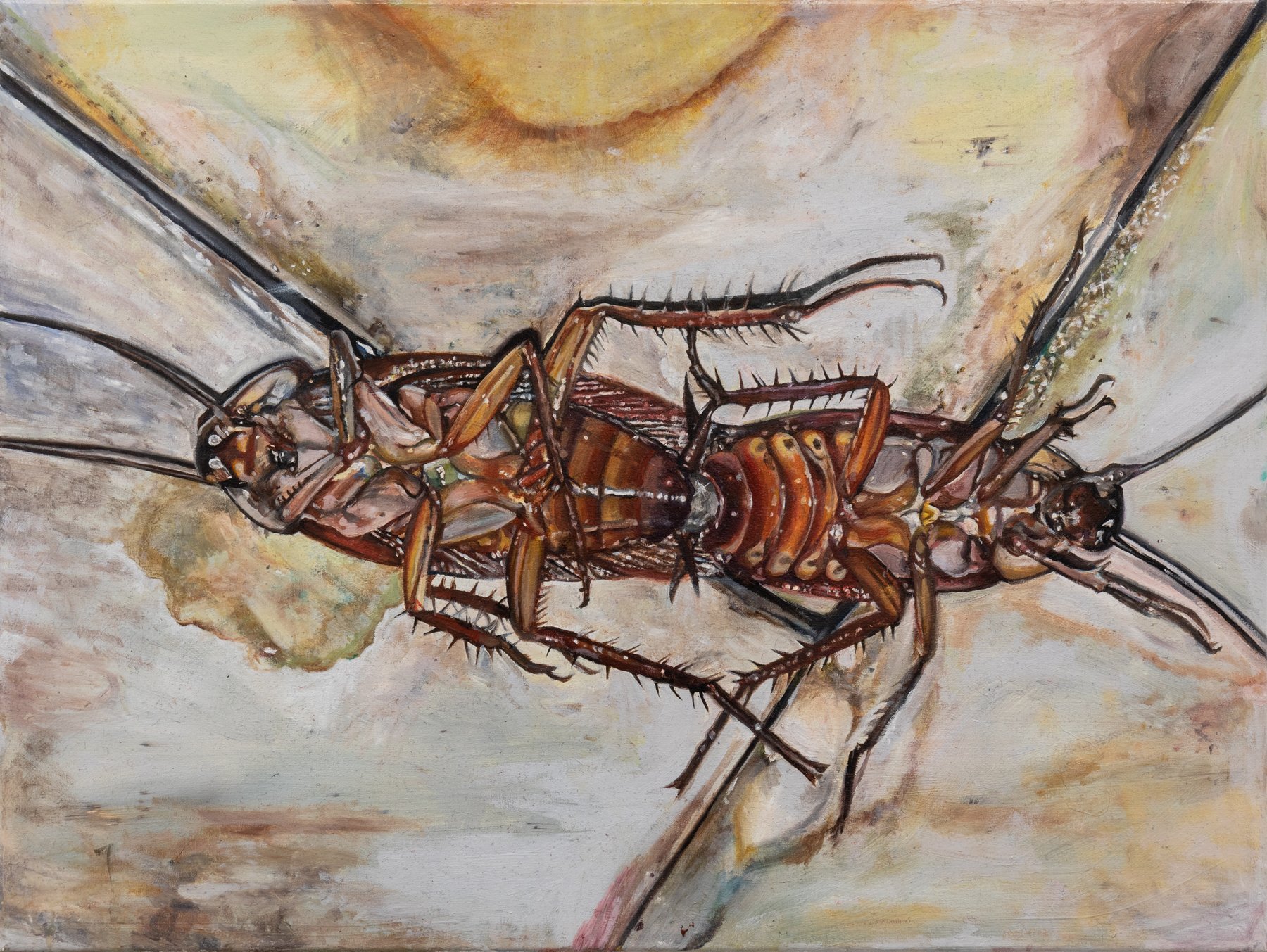

Rea Burton, Touching, 2021, oil on linen, 25.5 x 30 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Robert Heald

Becky Hemus: Your exhibition at Robert Heald is called Mates. Can you tell me more about the title? Are there any artworks that have an interesting backstory?

Rea Burton: I chose the title Mates because of its double meaning. It refers to the kiwi vernacular for ‘friends’ and also a pair of animals (in this case pests) having sex. I went with this title because I liked the humor, and that it could be read as kind of rude, like I’m referring to my friends as rats and cockroaches. None of the paintings in this show have personal backstories, in fact this is perhaps one of the main shifts from my previous work. There is a mundane correspondence between my painterly reproduction of the source image and the sexual reproduction they depict. I wanted Mates to be a bestiary of sorts, a symbolic language of animals. Using the idea of the ‘pest’ to symbolise some of the darker material realities that ground the cultural practice of visual arts production and reproduction.

Can you extrapolate further on the idea of the ‘pest,’ and these ‘darker material realities?’ The cockroaches and the flies in particular feel like vignettes of Gothic interior landscapes, a kind of damp, bug-infested reality of urban life in Aotearoa.

Nice, that’s one possible reading. There is an emptiness in the work that allows for many possible interpretations. One friend read the work as some kind sexual pathology, like it was about my sex life and how the act can feel disgusting and dirty. I found that interesting, even when I try to remove my subjectivity it’s hard to escape it. Personally, I was thinking about how what defines the ‘pest’ is sometimes nebulous. The ‘dark realities’ could refer to how the work might circulate, economic power relations, the issue of colonisation etc. The pest is an introduced species, which is maligned and unwanted, this becomes more complex when you take into account the anthropomorphising that is likely to happen. Although, the work will always exceed these significations anyway.

The titles are really interesting. The paintings that clearly depict animals are named quite playfully with phrases like Catfish, or actions such as Perseverance or Touching. Then there is White Rat, hard to discern at first because the creature has been sliced open, so the naming of him becomes more explanatory. Friend-Foe-Toe and Sex Pest look like human body parts. These two stand out because they are very uncanny, quite scary because they are kind of sexy and explicit, but then you realise they are strange and isolated animal parts. Where did you source your imagery from? Was there something you were looking for to capture what you wanted to present in the exhibition, or did you modify the images as prepared to paint them?

The research was quite compulsive, I have hundreds of screenshots from some animal mating videos and images from books. In the end I decided to go with something more ambiguous. That’s why the fucking images are all depicting insects, I thought that was more interesting. I took some liberties with the images and titled the works in a similar manner, to set up the way in which the work might be received.

Has anything you’ve seen or read recently influenced the way you think about your work?

Obviously we have completely different practices, but I’ve been really into Andrea Fraser’s ideas lately. I find her reflexivity interesting because of the kind of painful self-disclosure that is present in her work. There is always this deliberate compromising or undermining of herself, revealing certain power relations that are embedded in art’s production and reception.

Something that feels like a thread in your paintings is their tactility. The paint surfaces combine heavily mottled, impasto areas, and lightly blended brushwork. In previous artworks, there might be rope suspending the paintings in space, straw that looks like a bird’s nest, or wire loops framing a canvas. The skin and fabrics are patchy or striated in a way that evokes texture or sumptuousness. I often feel like if you pressed an area of paint, the shadows would move. There is something mildly grotesque about this, a sense of contagion perhaps. How do you view the way that your paintings spill out into the environment around them, and their relationship to your sculptures?

I’m not really interested in making sculpture anymore. There’s a lot of great energy around figurative painting at the moment, and working within the confines of its conventions feels like enough for now. The grotesque is definitely something that has always been present and evolving in the work. I think that the crude tactility of paint that you have identified has remained. The fundamental change is that the figures are no longer coming from my imagination. There is still a psychological aspect, but it is more to do with my selection of images and the treatment of the images through my painting process.

In your paintings from recent years, some of the figures are crying or gushing milk, but the liquid is very blocky. It’s more of a squirt than a drip. There’s a sense of reclamation that also feels present in the way you reference art history or utilise colours that clash. Is there a sense of defiance or subversiveness in the way you work?

I would say my work is more perverse than subversive. The paintings harness my personal desires in a way that might put myself and the audience into a compromising position. There is something quite ruthless about spending so much time labouring over a painting for it to get judged in an instant. I’m interested in work that ties to do something behind the audience’s back.

Can you elaborate on what it means to do something behind the audience’s back, do you mean that there are tricks within the canvas?

Essentially I just mean some kind of critique of the audience/framework of the artwork’s presentation, although I am not exactly sure my work functions in this way. In my case, I think the trick is more to do with lack. It’s the painterly mechanics of setting the parameters for how the work produces meaning, so by projecting onto the painting, the viewer might be caught by their own desire.

You have incredible style, and I often think this is something that plays out in your art. The figures are sometimes quite carnivalesque. They wear collars, bows, furry gloves, are draped in star-spangled fabric and don clunky boots. These aren’t necessarily outfits you would wear, but they are playful and draw out various references in a way that feels timeless. What are some touchstones for the garments in your paintings?

Thank you! I don’t think there is a direct relationship between my personal style and my work. Like I’m not trying to make work that is fashionable or cool! For me, it’s important for art to criticise these values, which might explain why I am drawn to taboo or grotesque subjects. I would say the slightly campy, theatrical garments in some of my previous paintings were related to this negation of personal taste and fashion. Florine Stettheimer is an ultimate favourite of mine because her idiosyncratic painting style was simultaneously serious and scandalous.

I first saw your work at a Window exhibition in 2016, like a dog and a bitch on heat. Since then you have shown regularly with Ivan Anthony and now Robert Heald, but also exhibit at artist-run spaces like Neo Gracie. Are the types of exhibitions you conceive different, depending on who the audience might be?

I don’t think so, no. The work isn’t really site-specific. The audience might be different within a dealer framework, but I think both spaces have critical potential.

Rea Burton, Sex Pest, 2021, oil on canvas, 45 x 35 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Robert Heald

“The grotesque is definitely something that has always been present and evolving in the work. I think that the crude tactility of paint that you have identified has remained. The fundamental change is that the figures are no longer coming from my imagination. There is still a psychological aspect, but it is more to do with my selection of images and the treatment of the images through my painting process.”

Rea Burton, Mates. Installation view, Robert Heald, March 2021

Rea Burton, Catfish, 2021, oil on canvas, 20 x 25 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Robert Heald

Rea Burton, Friend-Foe-Toe, 2021, oil on canvas, 45 x 35 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Robert Heald

Rea Burton, Love Object, 2021, oil on canvas, 24.5 x 30 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Robert Heald

Rea Burton, Touché, 2020, oil on canvas, 45 x 60 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Robert Heald

Rea Burton, Mates. Installation view, Robert Heald, March 2021

Rea Burton, Mates. Installation view, Robert Heald, March 2021

Rea Burton, Flinte, 2020, oil on canvas, 23 x 30 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Neo Gracie

Rea Burton, Instagram post, September 2020. Courtesy of the artist

Rea Burton, Farmers Daughter, 2020, oil on canvas, 23 x 30 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Neo Gracie

Rea Burton, Self portrait 25 Blushing, 2019, oil on canvas, oil, flashe and glitter on canvas, artist frame (steel, wire, enamel), 120 x 170 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Ivan Anthony

Rea Burton, Mates, Robert Heald, 4–27 March 2021

Julia Craig on Owen Connors’ egg tempera paintings.