Wet Green presents Ronan Lee

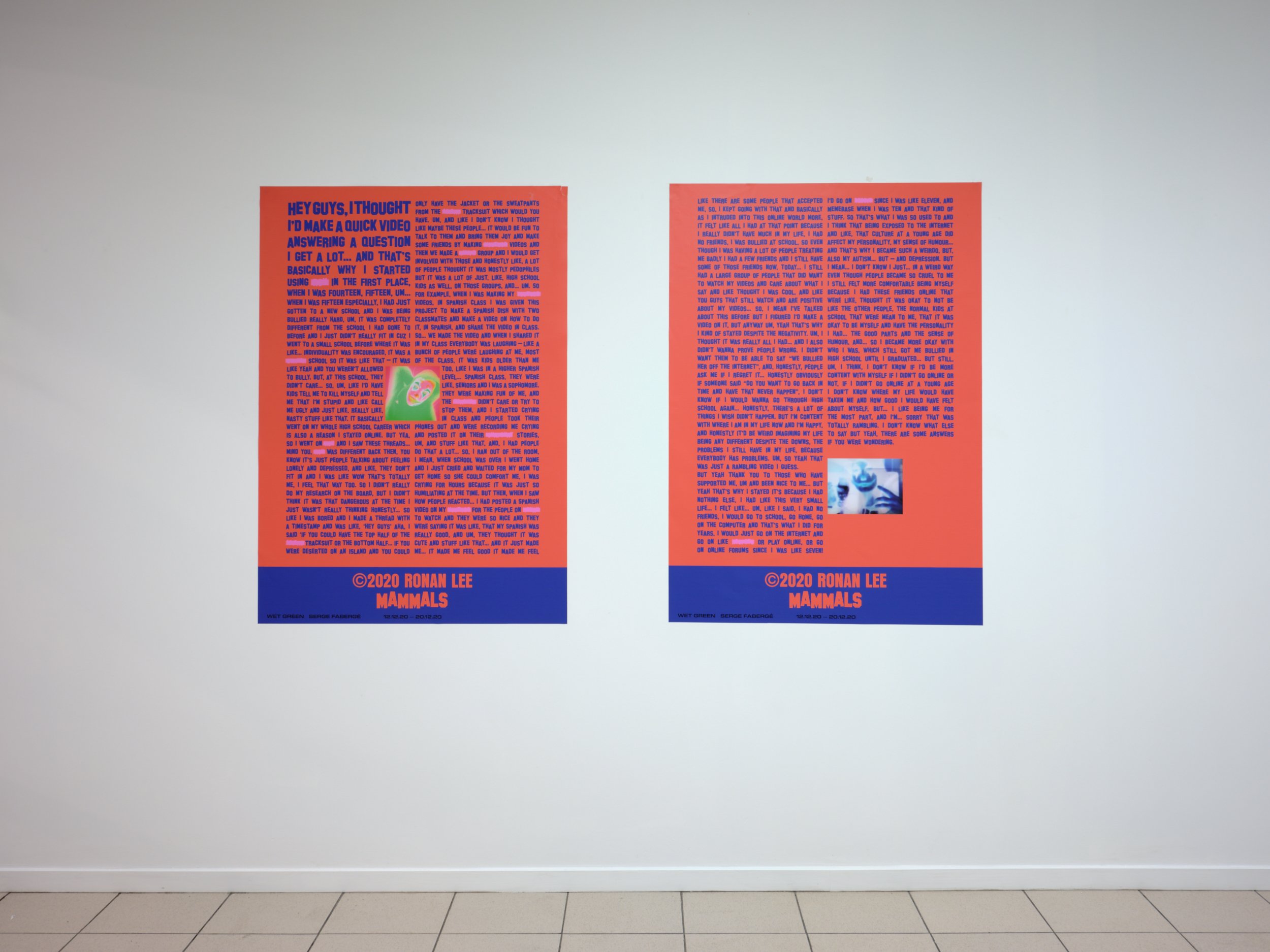

Ronan Lee, Mammals. Installation view, Wet Green, December 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Wet Green. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Wet Green is an artist-run gallery helmed by Becky Hemus and Eleanor Woodhouse in Auckland. We sat down with the pair to find out more about Wet Green and their current show Mammals by Ronan Lee.

Adam Bryce: What is Wet Green?

Eleanor Woodhouse: We call Wet Green a “gallery project.” We don’t have a permanent space but we put on shows intermittently, when we can and where we can. This inconsistency brings its own difficulties but it does mean we can take our time and tailor each project, especially around factors like location. Our first project, almost a year ago, was a feverish, chaotic performance that took place in our friend’s empty apartment.

You could also call Wet Green an artist-run space even though neither of us are strictly artists. But like artist-run initiatives (ARIs), we exist mostly off enthusiasm and our own unpaid labour, and show artists who are earlier in their careers and aren’t (yet) represented by a commercial gallery.

Ronan Lee, Mammals. Installation view, Wet Green, December 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Wet Green. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Ronan Lee, Mammals. Installation view, Wet Green, December 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Wet Green. Photo: Sam Hartnett

How did it begin?

Becky Hemus: In June 2019 I was in London and attended a Susan Cianciolo exhibition opening with friends. Through them, I met a gorgeous woman called Hannah. She was wearing an incredible dress that she had designed herself, and we started speaking about how she had originally studied fashion but had also just completed her Masters in Sculpture at the Royal College of Arts.

We talked about her practice and the synergies between art and clothing, as well as ideas surrounding the gothic, domesticity, and garments as traces of our lives. I was coincidentally writing my art history thesis on something similar at the time, and so many of our discussions became really pivotal in crystallising my thinking around these topics. We became close friends within a few days and both filed away an abstract plan to collaborate on an exhibition when we were next in the same city (which seemed like it might not happen for years).

A few months later, Hannah sent me an Instagram message saying that she was coming to Auckland. Eleanor and I went out to breakfast and I showed her all the images I could find of Hannah’s practice, as well as stills from films and links to books that Hannah had been reading. It turns out that they were both collecting some of the same inspiration imagery and watching the same films. Eleanor also loved Hannah’s artworks. I asked Eleanor if she wanted to help organise an exhibition/performance of Hannah’s work with me, and launch our much-talked-about gallery project at the same time. Of course she did, and then ensued a furious six weeks of exhibition planning, website design and brainstorming.

The name Wet Green was an amalgamation of so many things. We wanted a name that could be serious but also slightly irreverent and absurd. I wanted it to be a bit sexy, but maybe in a dank way. We are two women who are passionate about helping realise artistic projects, and it’s our first run at doing something like this together so of course we are a little wet and a little green.

EW: Becky and I had been talking about starting a gallery for years but never in any serious way. And it might never have happened except for the fact that an opportunity presented itself and we seized it when we could. Becky had visited London partway through 2019 and met Hannah Maria Schmutterer, a German artist and fashion designer, whose work she fell in love with. Becky came back to New Zealand raving about her. Then, a few months later, Hannah very suddenly had to come to New Zealand. She was going to be here for the summer and Becky said, “let’s start a gallery so we can show her here.” So we did.

Ronan Lee, Mammals. Installation view, Wet Green, December 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Wet Green. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Ronan Lee, Institutional Formalism (text), 2020, 2 x poster prints 119 x 84.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Wet Green. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Tell me about your views on the future of New Zealand art and why it’s so important to have artist-run galleries such as Wet Green.

BH: The future is bright. There are so many artists and collectives doing interesting things. Each space that operates outside the commercial dealer gallery model is completely unique in terms of how they are funded, their programming, the frequency of exhibitions. When Eleanor and I established May Fair Art Fair earlier this year alongside Ophelia King and Nina Lloyd, it dawned on us just how many curators and spaces operate independently without wider visibility from the public.

A lot of the art that is shown at ARIs is slightly more experimental as it’s often made with a non-commercial lens. Sometimes the pieces might not look incredibly polished as there simply hasn’t been the money to realise them in this way, but there is a vibrancy to the process and way they are exhibited which is exciting. ARIs aren’t relying on income from sales as they are often approached as care projects rather than full-time jobs. And I think inevitably this contributes to a different kind of art-making.

Our process with Wet Green is to provide end-to-end support. Our exhibition with Ronan Lee is the first time that he has been able to work alongside a professional framer and make decisions around the precise finishes of each piece. We have less projects than other spaces (and no permanent address) but we put a lot of time and consideration into each exhibition to help our artists realise something different from what they might have been able to previously.

I do think that the operative word here is care—any space needs to care for their artists and the communities they operate within. With ARIs specifically, there are possibly less checks and balances, but we are always accountable to the people around us. It’s important to remember this and keep asking what kind of art ecology we are wanting to contribute to.

EW: I think the future of New Zealand art is much the same as the history of New Zealand art, it’s always a struggle. A struggle for artists to be able to produce work while making a living, and a struggle for galleries to break even. This is true all around the world but I do think New Zealand is uniquely challenging because of our small size. There are only so many wealthy patrons or collectors, with only so much wall space here, so it’s hard to keep the system going.

The importance of artist-run initiatives is obvious—you need galleries if you want art to be made and experienced. And if you are only accessing art that’s shown at commercial galleries or institutions, that’s quite limiting. There are so many young and unrepresented artists who have incredible practices but who just can’t be accommodated by our relatively few dealer galleries. ARIs allow them to show and allow the public access to their work. It’s a flawed system though, generally ARIs are run on love and donated time, which is unsustainable.

Ronan Lee, Democratic Materialism; excerpts and additions, after People of Colour, Mercy Pictures, 16.10.2020–07.11.2020 (detail), 2020, coloured lighting gels; epoxy resin; found bucket and mixed media, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Wet Green. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Ronan Lee, Mammals. Installation view, Wet Green, December 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Wet Green. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Can you describe Ronan Lee’s work?

EW: I think Ronan’s work is easily misunderstood—it’s often beautiful, always somewhat obscure, and kind of confrontational. His current show includes, among a series of sublime photographs of animals, a Kermit the Frog soft toy who’s hanging from gallows, and fake feces in a bucket. Ronan appears to be a bit of a troll, but underneath the obviously trollish gestures is actually a lot of careful thought. Nothing about a Ronan Lee show is incidental even if it appears so at first glance.

Ronan’s work is obsessed with internet cultures and our current socio-political-cultural clusterfuck. I usually don’t like art about the internet, there’s something about trying to visually represent the digital in a non-digital medium that’s kind of corny to me. But Ronan makes work about digital cultures that doesn’t try to replicate interfaces or the appearance of the internet. He addresses it in more sophisticated ways. The nuance in his work can take some effort to appreciate, but it’s worth getting there.

But if you don’t get there that’s okay, unlike a lot of artists, I think Ronan doesn’t mind being misunderstood.

BH: Ronan is a very performative artist, but in a way that attempts to defy the more sparkly personas of the male canon like Joseph Beuys or Jeff Koons. He’s very evasive and quite open about this. There are a lot of hidden layers and artifice in his artworks—fake poo, fake raindrops, laborious casts of things that look like rubbish. His art appears uneasy, but that’s how I believe our contemporary, internet-mediated culture functions. There’s always something to hide behind and there’s always someone who doesn’t really know what they are talking about but is able to have some kind of platform regardless.

Ronan has said that most art dealing with politics does so as a surrogate for philanthropic gestures. We can talk about the climate or concerns around internet subcultures and surveillance, but if we do this in a way that only makes the audience feel good and virtuous for having taken the time, then what does it achieve? I don’t know if Ronan’s work achieves anything either, but I do find his approach interesting.

Ronan Lee, ... rings the bell one-a-penny two-a-penny hot cross buns! (Fred learns to spell) / For Chatterbox Zombie, 2020, mixed media, 110 x 88 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Wet Green. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Ronan Lee, Mammals. Installation view, Wet Green, December 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Wet Green. Photo: Sam Hartnett

And this exhibition Mammals, in particular?

EW: The main works in Mammals, ten framed photographs of exotic animals, is a continuation of the series Ideological Drift, which he’s been working on for a few years. The series started with photographs of celebrities—(sub)cultural icons like Beth Ditto or Dash Snow—which had been rephotographed by Ronan and distorted, and then the frames and glass would be covered in raindrops. The droplets look real but they’re actually made out of resin, so they’re frozen in place forever.

In Mammals, Ronan’s moved from celebrities to animals—which isn’t a break, more like a continuation. The images are taken from wildlife photography books, and again Ronan’s distorted them and covered them in resin rain. The raindrops are incredibly beautiful, but they’re also melancholy. They obscure the photographs, and I see them as a metaphor for the barriers that obscure our understanding of the world and others, and obscure connections with others.

That’s a theme of the show overall—the loneliness and isolation of life online and in real life, our multiple subjectivities, looking at subjects we can’t fully know or understand, not being understood ourselves. Somehow, though, the show is also funny, and cool, and fun. I love Ronan’s work because I love art that’s both poignant and funny, fun and sad.

Ronan Lee, Democratic Materialism; excerpts and additions, after People of Colour, Mercy Pictures, 16.10.2020–07.11.2020 (detail), 2020, coloured lighting gels; epoxy resin; found bucket and mixed media, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Wet Green. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Ronan Lee, Mammals. Installation view, Wet Green, December 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Wet Green. Photo: Sam Hartnett

What’s coming in 2021 for Wet Green?

BH: More gallery iterations with artists whose work compels us. We are hoping to exhibit at the Auckland Art Fair with a solo presentation by Priscilla Rose Howe, and are also in the midst of planning a fashion-related exhibition with another artist who we both love. It’s interesting to see the synergies emerge between our projects as Wet Green develops.

EW: We’re starting the year off with a presentation at the Auckland Art Fair in February—well, hopefully. We’re in the middle of a Boosted campaign to raise funds so we can participate. But all going well we will be showing Priscilla Howe, an incredible artist from Ōtautahi who draws these surreal scenes populated by strange, sinister-yet-charismatic characters.

We are also in the early stages of planning a more experimental curatorial project, involving performance and film, with an artist who’s wanting to explore aspects of their practice that they haven’t had the opportunity to develop before.

Wet Green will also be taking part in the next iteration of May Fair. Because of Covid, the first fair had to be entirely online, so we’re looking forward to bringing it into physical space for the first time.

You can help Wet Green and other artist-run galleries take part in the Auckland Art Fair 2021 by donating to their boosted campaign here.

This article originally appeared on our sibling website, Index

Olivia Renouf visits the City Ceremony opening party, a collaborative exhibition and pop-up at The Art Paper HQ, feat. designers Baobei, Byskinny, Companion, Jess Grindell, Taylor Groves, Emma Jing, Alice Langbrown, RGK, Stockist, and more; and artworks by Zoë Gow, Ronan Lee, Ali Senescall, and August Ward.