In Conversation with Sione Faletau

Gus Fisher Gallery Director Lisa Beauchamp speaks to Sione Faletau about audio waves, the practice of performance, and looking toward the concept of vā as a way to encapsulate or engulf space. Produced in partnership with Gus Fisher Gallery on the occasion of the exhibition Turning a page, starting a chapter, through 9 July 2022.

Sione Faletau, Ongo Ongo (still), 2022, digital video. Courtesy of the artist

Lisa Beauchamp: Before we talk about your work in Turning a page, starting a chapter, I want to circle back to your New Graduate Works exhibition at Gus Fisher Gallery while you were studying at Elam. Since then, your work has gone through quite a few different iterations. You entered Elam as a painter but for the show in 2014 you exhibited a film that documented a performance. I wonder if you could talk about your evolution from painting to performance and film.

Sione Faletau: My piece in the New Graduate Works in 2014 was an exploration of my Tongan heritage during my Masters. I was looking at the sacredness of the Tongan body, juxtaposing different body adornments that were made for women and for men but placing women's objects on men's bodies. I went through the motions of entering Elam as a painter and then getting into performance and video. I went solidly into performance and video in my Masters. In my Doctoral year my work just changed into this digital form. The way I work is to try and find the faster way of doing things, what's efficient for me. So it's that process of finding ways I could push out ideas as fast as I can. I went through those motions to find that workflow. There's this journey of discovering things.

You mentioned that as you started to explore more of a cultural tradition, and specifically your Tongan culture, that led you to different mediums. How did you then shift from performance towards film?

It was a way to document my performances, just like my sketch ideas. I mainly did live performance, but I was told that if there was no documentation of the performance then did the performance really happen? I was just using video to record my thinking and my practice and then eventually it did become a thing where I was presenting work as documented pieces. I found it organic, like Bruce Nauman in the studio mapping out or scanning his wall or a space. All that stuff is documenting his thinking and his practice. I took that on board as well, having a record that the performances did actually happen.

So film for you was more of a documentary tool. When did that shift occur when you began to focus on film and then moved into your digital practice?

During lockdown. When I was getting into my doctorate I started becoming more focused with my performance and [looking into] ways I could be more in control of things. For example, in the lighting studio at Elam I could control and document the environment. But I couldn't be in the lighting studio and other university studios [during lockdown]. We were given a computer to use, and again, this began the process of getting out my ideas. Initially there were all these performance ideas that I was sketching down. I was doing it digitally through different applications and also using sound. Sound is a strong part of my art practice and performance. I've used live drumming. Tongan drumming and sound stuck with me. I started exploring the sound aspect and this is where I'm at now with my practice.

It’s interesting that sound has been a continual interest throughout your performance practice and now your digital film practice. Would you say audio has become one of your central focuses now?

Yeah, definitely. It has become more centralised in everything I'm doing. If I'm going about my day I'm really conscious about what I'm hearing and I'm just trying to channel into that. I think it's taken over my life.

Being in lockdown you're very aware of the silences and of the sound around you. You're in a different environment because you can't go out and mingle with people. There's less people on the street. Has that shift in environment enhanced the way that you think of audio?

When one sense is taken away, the others are definitely heightened. The lockdown environment changed my thinking and my approach to sound a lot. I was always conscious of dealing with sound as we're surrounded by it 24/7. Even silence has its own sound.

That brings us to your current practice and the works you produced for Turning a page, starting a chapter. Ongo Ongo consists of audio you've collected in the gallery space. This work is symbolic of how you're currently working in that you're using sound almost as your sketchbook to influence what the work will become. Is that a good way of putting it?

There's a freedom in using sound. I could let it free and be in control at the same time, which gives me freedom.

With Ongo Ongo, the sound and the visuals are intertwined and they spark each other. I know when I first approached you, you wanted to come into the gallery and you wanted to capture the vā of the space. Vā as the space in between things. Can you talk about the process that you went through; and what was your thinking in how you were going to capture that environment?

I think of sound as a vā. It's an environment that encapsulates and engulfs a space. Within Oceanic cultures, and especially within my Tongan culture, sound precedes the ceremony. There's kalanga or drumming that signifies the start or end of a ceremony. The vā that Gus Fisher Gallery has also has a relationship to the outside world. There's a communicative relationship that the gallery once had with the environment, the people, and New Zealand at large. I was thinking about those histories as well as future relationships to the public. It's through educating people on art or creating programmes and exhibitions and things like that. So the process of just sitting in the space and capturing the day's events, people coming into the space, in the vā of the gallery, I wanted to capture that through sound. You can hear a door slamming and people walking in. You can hear the hum of the city as well. There’s contrasting sounds from the CBD and you have the quietness and the steadiness of the gallery. Those were my little thought processes on how I approached the vā for this work. A large part of it is to do with the broadcasting histories and what's been there and honouring what was there and what's to come in the future.

Let's talk about the technical aspects to making your work. What happens once you've made a sound recording?

I want to keep everything organic when it goes into the editing process, unless there's something I want to curate out of the sound. Mostly for Ongo Ongo there was no editing done to the audio. Once I get the recording, it goes through a music production programme (I use Logic and Audacity) and it's through these programmes that I can see the data visually. It immediately gives me a visual for the different spectrums of the sound. From there it goes into a programme called After Effects. That's where I start creating the kupesi or patterns. At some point with this artwork I started playing around with algorithms and coding that you can punch into After Effects that would generate kupesi within a certain frequency or angles. What I identified within geometric kupesi was that it was occurring around angles of 30 to 45 degrees. It was these clues and figures that I could generate into the digital space to create the visuals.

What inspires you to create the patterns that you do? Is it partially the audio data or do you have a set idea of the types of patterns that you want to create?

I start implementing the algorithm that gives the patterns parameters to generate within. But initially it's always organic with the kupesi. I let the audio waves form their own patterns and sometimes all of a sudden these patterns are showing up and it's like, "Hey, where did this come from?" But generally I'm letting the audio waves generate their own pattern.

I think back to your work in performance which is often organic or can be difficult to control. Maybe there's that organic sense of flow or sense of experimentation. You've got control over it, but you're also open to it taking its own form.

Absolutely. I think it just speaks to that freedom, just seeing things flow but at the same time you can pull it back. Beautiful things happen when you let things go. There are those two aspects: control and freedom.

What's so mesmerising about your videos is the way they continually fluctuate and move and how all these patterns merge into one another. They're quite hypnotic when you're looking at them. With Ongo Ongo, I immediately saw a connection between the kupesi and the Dome Gallery [in Gus Fisher Gallery] where you have repeated patterns on the ceiling of the space and motifs of radio waves on the doors and windows. Site responsiveness is also key to your practice. The audio is collected onsite but then the resulting visuals have a connection as well.

When you showed me all those embellishments on the windows and door frames it really spoke to me and the work that I was creating. Again, it was that organic thing that I was letting happen. The work definitely had an Art Deco aspect to it and really spoke to the architecture as well, especially with the Dome Gallery.

I want to talk briefly about Tolu Katea, an existing video on loop with Ongo Ongo. It features a beautiful choir of voices that synchronises with the visuals. The audio is very different as you haven't collected it onsite. What was your thinking in making that work?

When I was creating Tolu Katea it was more the singing aspect that intrigued me. The voices are a controlled entity, the way that the choir sings together. The freedom with the ambient noise and environment recordings that I have made in the past is totally different. I found that when I started working with voices, I tried to find the parts where there's a lot of activity happening in the audio wave spectrum. That gave me a bit of structure to work with. It was like finding aspects of the audio waves where there was a lot of activity within the three frequencies of voices; the high, medium and low. That approach was more so to do with the voices and where I could see a lot of activity happening. There was a bit more control in that work.

Can you talk about the meaning of the hymn as well and what they are singing about.

They're singing Eiki koe ‘Ofa A’Au, which talks about God's love as a big ocean or the vast moana. It's really talking to the spiritual side of being Tongan. There's a spiritual element to all of us, whether we're conscious of it or not. There's often a neglect of the spiritual side of humans. We always have the mental and physical sides, but the spiritual is often left out. For this piece I was looking at the spiritual vā within Tongan culture.

You’ve recently completed a project at Britomart and you've exhibited at Masons Screen in Wellington. You mentioned at the beginning of our conversation that your practice moves quite fast. As you continue to progress, how do you see your digital practice developing? Do you think you'll continue with this way of working or now that we're out of lockdown have you been thinking about performance again?

Yes, performance is definitely back on the agenda. I'd love to start exploring performance and adding the digital side to the repertoire of my art practice. I've always been conscious of creating performance around kupesi. I've been talking with choreographers as well, so my performance mind is totally back. As you said, sound has encapsulated my approach to making. My art practice revolves around sound right now, but the performance side is back. Hopefully I get to create some performances in the near future. Maybe in a month or two.

That's really exciting. I think there's so many interconnected strands that we could talk about, but I think it's great that performance could be making a comeback. I can't wait to see what you do.

Sione Faletau, Tolu Katea (still), 2021, digital video. Courtesy of the artist

Sione Faletau, Tolu Katea (still), 2021, digital video. Courtesy of the artist

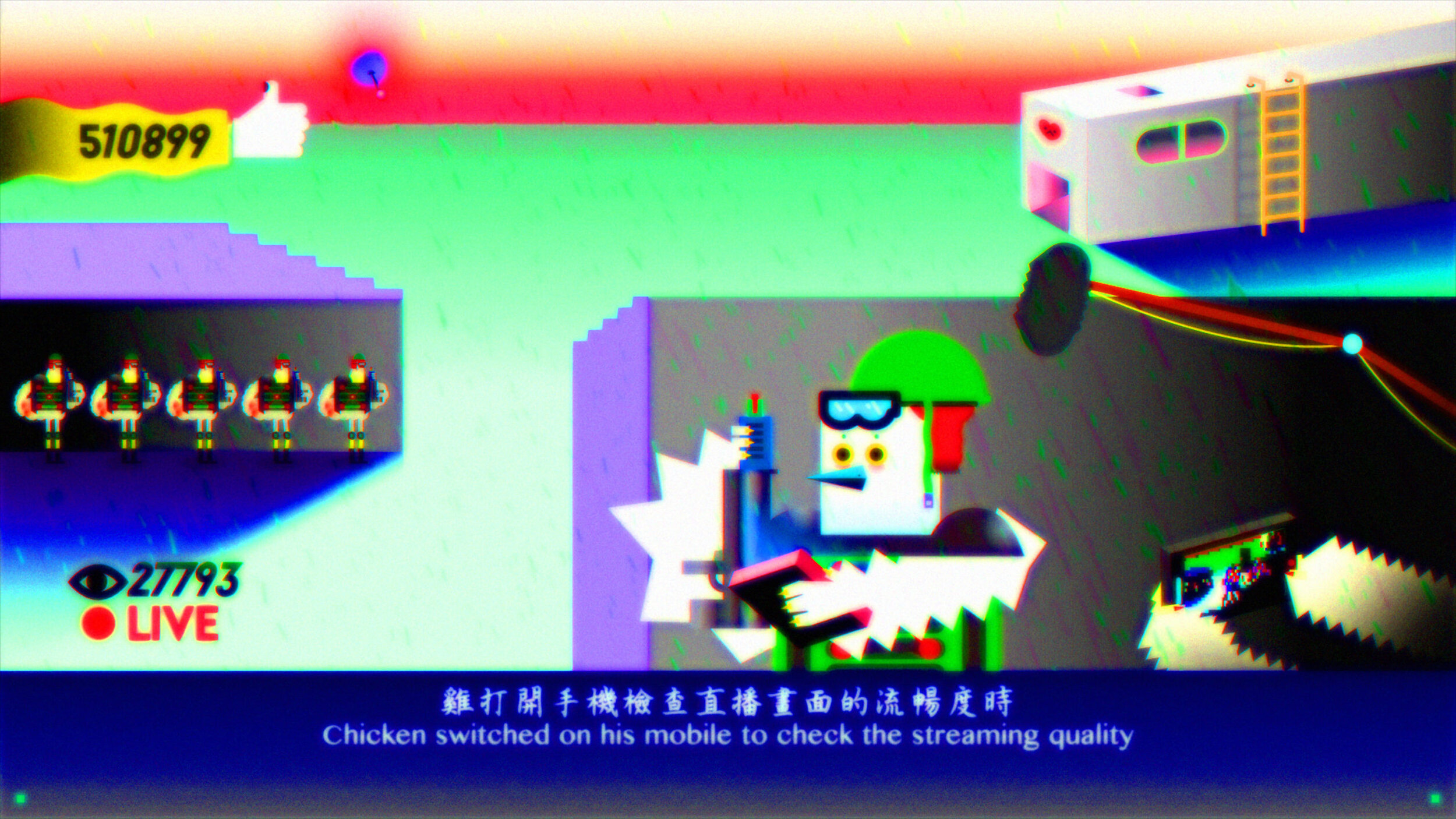

Sione Faletau, Ongo Ongo (still), 2022, digital video. Courtesy of the artist

Sione Faletau, Ongo Ongo (still), 2022, digital video. Courtesy of the artist

Sione Faletau, Ongo Ongo (still), 2022, digital video. Courtesy of the artist

Sione Faletau, Ongo Ongo (still), 2022, digital video. Courtesy of the artist

Connie Brown on Simon Denny and Karamia Müller’s Creation Stories, Michael Lett, 6 August – 10 September 2022; and Gus Fisher Gallery, 6 August – 22 October 2022.