Hard Limits: on Hikalu Clarke’s Dredge

Gallerist Dan du Bern of Sumer on Hikalu Clarke’s current exhibition at the gallery.

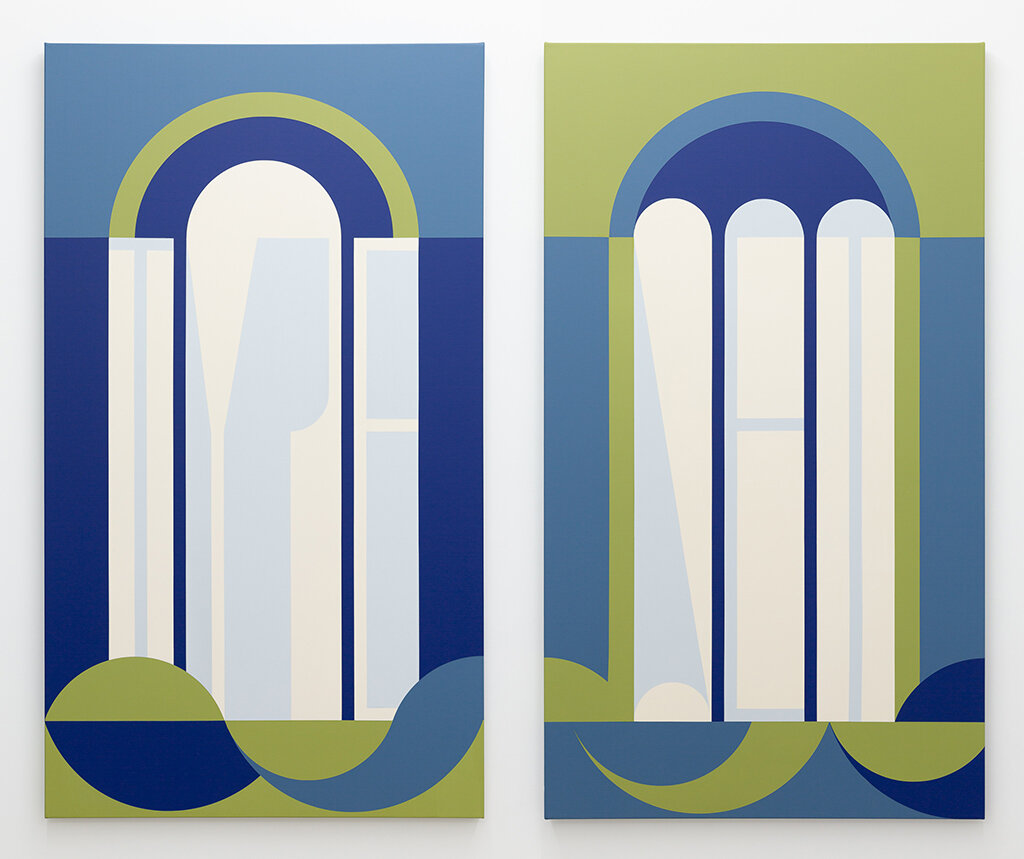

Hikalu Clarke, Dredge. Installation view, Sumer, Tauranga, August 2022

The living room of his Newton flat, which doubles as his artist studio, looks out over a section of Auckland’s elevated motorways where three major arterial roads converge. These monumental structures of concrete and steel twist upon themselves as if they were gigantic snakes, writhing and constricting. Connecting the south, west and north, each day they funnel tens of thousands of passengers, and many thousands of tonnes of goods, in, out, and through the city. The dominating physical presence of these structures cleave their way through the inner suburbs, violently and abruptly rupturing their immediate surrounds. Carving up the spaces, effectively creating barriers and would-be no man’s lands. This could be a view from any number of modern cities across the globe. It is one which is at once spectacular, awesome—surely a marvel of modern engineering and technological advancement—and yet equally brutal, ugly, and thoroughly dehumanising.

I’m here on the advice of a good friend, to meet with young artist Hikalu Clarke and see works that he’s made over the past two years. Pieces made whilst the country, and this city most acutely, was isolating under a series of successive and persistent lockdowns; that were made in what an outspoken former prime minister derisively surmised as our “hermit kingdom”.

From this elevated position, the road noise is an ever-present din that is not entirely dissimilar to the sound of a rough sea on the shore. I’ve been here a few times and the conversations that we have in this room are lively, energetic and free flowing, bouncing between topics broad and discursive—from art to theory, politics, fashion and partying. I also notice after a few visits that he always chooses to pull his windows right open, whereas his neighbours always seem to have theirs shut. Clarke speaks of how much he loves this flat; relishing its position, the view, AND the road noise, not to mention the debauched goings-ons from the street below.

The view from Clarke’s window reminds me of a scene from David Cronenberg’s 1996 film, Crash. Shot from the balcony of a high-rise apartment, which similarly looked down upon an expanse of multilane highways and interlinking overpasses, also with steady flows of fast-flowing traffic speeding through the frame. In the foreground the film’s protagonist James Ballard, in conversing with his wife Catherine, coolly states, “There seems to be three times as many cars as there were before the accident”.*

And yet in direct contrast to Ballard’s statement, I think about how strange and uncanny the view here must have been when Clarke began making these works under hard lockdown. The eerie quiet from empty roads, devoid of traffic. It would have been quite unlike any other time in living memory. In fact, the only comparable images are fictive, film scenes from post-apocalyptic thrillers such as 28 Days Later (2002), or more locally, The Quiet Earth (1985).

The works that line the walls of Clarke’s living room sit between conventional painting, quilts, and décollage. Clarke calls them paintings, despite not a drop of paint having been applied. They are constructions, made from a diverse but carefully selected range of fabrics—scraps of irregular size and shape. Some are old, others new. Fabrics that have been machine-stitched together in the main, in often narrow, sinuous lines running parallel and intersecting, opening out into broader sections of flat material, some patterned, others plain. There is an apparent haste in their manufacture, an odd loose thread here and there, a few frayed edges, popped seams—some that have been repaired with rough sutures, and others left as gaping holes. They are clearly elaborate labour-intensive constructions, but hardly careful, let alone neat. He winces when I suggest that they might be considered quilts. I had wondered if this was because it was too emasculating a proposition, but later decide it was more likely because it seemed too orderly, too traditional an art form to be an appropriate designation.

Of course, in considering they are stretched as you would a canvas, they certainly read as paintings. And such being the case, one is made to think of other types of painting: Desert paintings of Indigenous Australia—songlines, topographies, maps. Also art informel—post-war Europe’s answer to abstract expressionism. (Think abstraction with the trauma and nihilism that comes with surviving war and remaining in bomb scarred cities.) In particular, the work of Alberto Burri—similarly spiderweb-like, and also degraded. And yet Clarke’s are less outwardly brutal, less povera, in their use of materials and palette. They are altogether more current in terms of technology (high-vis retroreflective coated polyester, fire-retardant aramid, carbon-kevlar, and heavy vinyl used for at-risk prisoner mattresses) and ethnocultural diversity (bolt ends of vintage Japanese print fabrics that would have been used in both kimono and soft furnishings). And whilst they are arguably no less aggressive or violent, there’s a delicateness and svelte quality in Clarke’s materials, as if they were cast-offs from high-end outdoors garments or hip couture. And thus, possess more obviously libidinal charge, reading more on the register of raunch and fetish cultures, as opposed to pure abjection.

Fashioned from cast-offs and remnants, as well as other bits and pieces he collected on his recent travels and things that were around the studio, their fabrication involved the dismembering of costumes used in past performances and previously exhibited soft sculptures. And for these reasons they elicited in Clarke a sense of unease; seeming almost sacrilegious, iconoclastic, or at the very least an act of self-sabotage, diminishing his own artistic legacy through such acts of destruction. This unease was also due in part to the fact that he set out without any clear sense of intent in the making of such works, at first lacking any clear understanding as to their specific meaning or purpose (beyond the merely decorative).

Inchoate, formless in image and meaning, yet not without intent and purpose, their making was an action more akin to physical activity or meditation rather than something dialectically oriented. This generative and intuitive process, this thinking-through- doing, was a clear shift for Clarke; whom he tells me had, up until this point, approached the making of work in a far more premeditated, codified and certain manner. Here he found himself making objects whose physical appearance was largely arbitrary, at least initially (defined mainly through chance); only later would he apply a judicious eye in arranging their compositions, and subsequent titling to elucidate their meaning further.

The second exhibition at Sumer, in late 2018, was titled The Widening Gyre; a title lifted from the first line of W. B. Yeats’ seminal poem, The Second Coming (dating from precisely one hundred years prior). It was a group show that brought together various artists from across New Zealand and Australia, whose work I felt typified key aspects within contemporary painting. Clarke’s work would have fitted well in this show. The focus was on paintings commonly murky and foreboding in palette and form, with a pervading sense of unease and uncertainty, yet captivating and beautiful nonetheless. A sullied spectacle. And now after living through two years of pandemic I am made to wonder if this titling was more prescient than I could have anticipated, or just emblematic of the fact that we live in a perpetual state of anxiety and instability, in which a fear of impending calamity pervades modern society wholly. Indeed I was hardly the first to reference Yeats’ poem, nor am I likely to be the last. Abridging the words of Donald Rumsfeld, we live in a world defined by those things that are, “known-knowns”, “known-unknowns”, and “unknown-unknowns”.

Clarke named this show Dredge, a shortening of his original intended title, Dredging the Mire (abandoned for not wanting it to be conflated with the similarly phrased Trumpian neologism). He did so as he felt it best described this process of making: of dragging up and carving out, refashioning and repurposing old things to serve new ends; to look upon things with fresh eyes. And by contrast, when I hear the word Dredge in relation to these works it too suggests its etymological relative “drag” (as well as the phonetically similar but unrelated “dread”). I think of his digs, just off K-Road. The retroreflective material, sewn with sections of shear, appearing like dead skin—cadavers in a mortuary—until the light hits them on a certain angle and then bang! clubkids, leather bars, ballrooms, thirst, sweat, hard limits. These are paintings of the city, even at the hours we think it is asleep.

* A film, based on the 1973 novel by J.G. Ballard, which chronicles a car crash victim and his partner as they stumble upon, and participate in a kink set who find sexual gratification in the witnessing and participation of automobile accidents, and their consequential bodily trauma and scarring. Whilst winning a special jury prize at Cannes on release, the film was highly controversial for its portrayal, with seeming ambivalence, of graphic sexualised violence.

Hikalu Clarke, Dredge. Installation view, Sumer, Tauranga, August 2022

Hikalu Clarke, You're Safe Now, 2022, retroreflective polyester, kevlar aramid, at-risk prisoner mattress fabric, cotton thread, 100 x 60 cm

Hikalu Clarke, You're Safe Now, 2022, retroreflective polyester, kevlar aramid, at-risk prisoner mattress fabric, cotton thread, 100 x 60 cm

Hikalu Clarke, At the Threshold (detail), 2022, retroreflective polyester, vintage Japanese fabrics, 157.5 x 254 cm

Hikalu Clarke, Dredge. Installation view, Sumer, Tauranga, August 2022

Hikalu Clarke, Autopilot, 2022, retroreflective polyester, 60 x 45 cm

Hikalu Clarke, Essential Services, 2021, retroreflective polyester, aramid kevlar, salvaged fabrics, cotton thread, 90 x 60 cm

Dredge runs at Sumer through 24 September 2022.

Gallerist Dan du Bern of Sumer on Hikalu Clarke’s current exhibition at the gallery.