Feigning Indifference: In conversation with Henry Curchod

Gallerist Dan du Bern discusses painting and its potency in contemporary culture with Australian artist Henry Curchod on the occasion of his exhibition Sharing the Sky at Sumer.

Henry Curchod, Sharing the Sky. Installation view, Sumer, Tauranga, August 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

Dan du Bern: Henry, I have to admit to stalling somewhat with starting this interview… Not because I didn’t have things to ask you about your work—hardly! Rather it’s that the two of us have been in regular correspondence for some time now, and thus it’s hard to know quite where to begin.

Henry Curchod: I’ve been looking forward to having a more formal discussion with you. We flick past so many themes in our interactions, which usually come in the forms of text messages, DMs and phone calls. It's rare to have an opportunity to break things down a bit. I guess that’s the beauty of making images, that so much can be said without having to be said, but sometimes things also need to be said.

The current circumstances have hardly made for plain sailing: the Delta variant—our bubble bursting. Lockdowns: first in Sydney, now here in Aotearoa. And there’s also those things which don’t involve us personally but affect us nonetheless—witnessing those poor wretches in Afghanistan, and the wildfires in the Mediterranean. In the midst of this, your new exhibition here at Sumer, Sharing the Sky, has also just opened.

I was thinking, the other day, about our current predicament, specifically in relation to the big auction houses. They define a genre of their auctions as ‘Post-war.’ Will they have ‘Post-pandemic’ auctions to bookend the vague and horizonless ‘Contemporary’ and ‘Post-internet’ genres? Or a ‘Post-climate’ auction? I guess these thoughts stem from a desire to bookend our current reality for the sake of morale. Perhaps it is fitting that the show depicts attempts at bookending gravity—a notoriously elusive and ever-present force—as a way of building a kind of metaphor for our struggle with the concept of freedom.

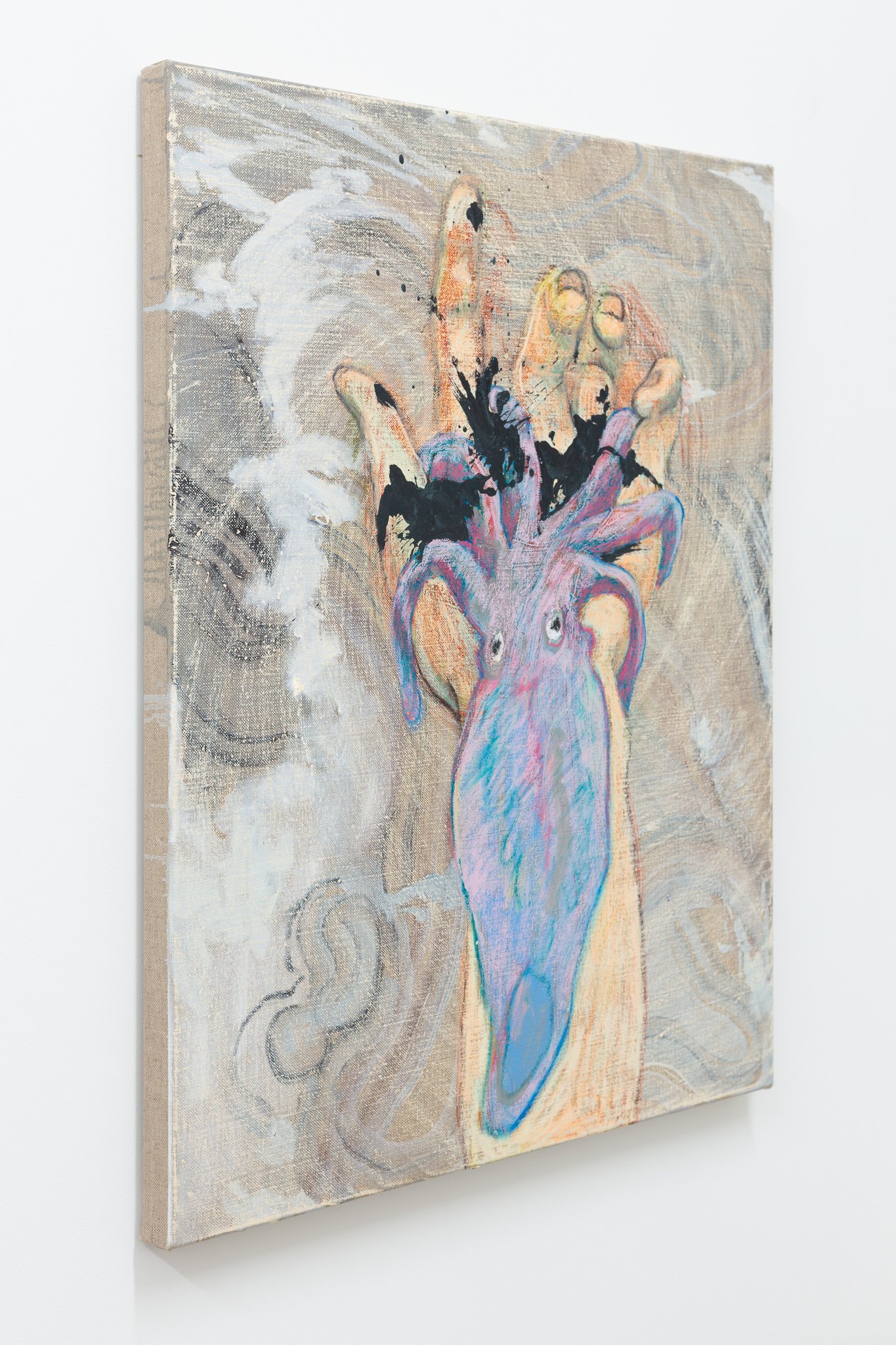

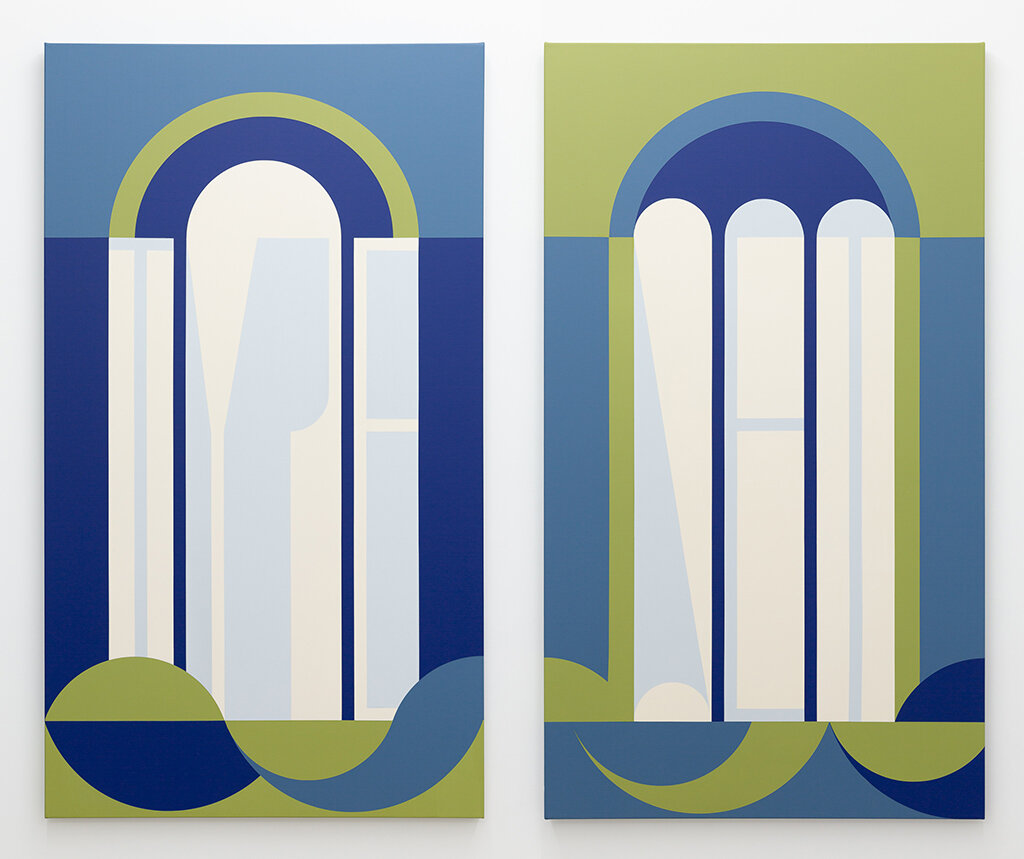

Sharing the Sky is your second at Sumer (third, if you also include the online viewing room we ran at the end of last year). The paintings in this show are different to those previous. The use of rough linen and oilstick is new. The palette is also different—brighter and cleaner than the earlier works. Louder, lurid perhaps? They seem altogether more playful and energetic. The paintings are less compositionally structured (the archway which framed previous works are all but absent now, and the veiling/meshes that defined many of the earlier works are also less apparent).

You also speak of them as drawings rather than paintings, why is this distinction important?

I was recently looking back at things I made before I went to art school. They were so drawing focused. Dirty, dark and naive; they had a spontaneity and absurdity that I missed. There’s something about drawing that allows for a playful approach to dark subjects. I find painting can struggle with this.

Six months ago I bought a pile of oil sticks. They are bizarre—solid but liquid at the same time. The idea was that I’d be able to get the things out of painting I love, and keep the fundamentals of drawing as a foundation for the imagery. So in a sense, I was treating this beautiful linen like scrap paper, and ended up making these big playful drawings. Half-way through the process I would change the way I used the oil stick, building up thick layers like a painting. That they landed in this place between drawing and painting. It made so much sense to me.

Drawing is so primal. And right now primal is very important. Getting to the core of things or reducing things to their bare necessities is a common theme in my life right now (as I’m sure it is for other people). So it’s not surprising that this has come out in my work. I’ve always been interested in ancient cave paintings, but I would argue that they were distinctly drawings. And ancient Persian miniatures, whilst they look like paintings, the paint is almost drawn on. In many cave ‘paintings,’ you can see every mark, they have such strong intent but a wilful vulnerability. The images are simple, but so powerful and evocative—they managed to get so much out of so little.

I also wanted to ask about the works and their subjects. Some are decidedly crude, in subject, title, or both, seeming almost juvenile, superficially at least. (Perhaps irreverent is a better adjective, well at least more respectful, but no they’re crude, I think you’d agree?). Meanwhile, other works are more elegant, sensual, and joyful. And others seem to sit all together more uneasily.

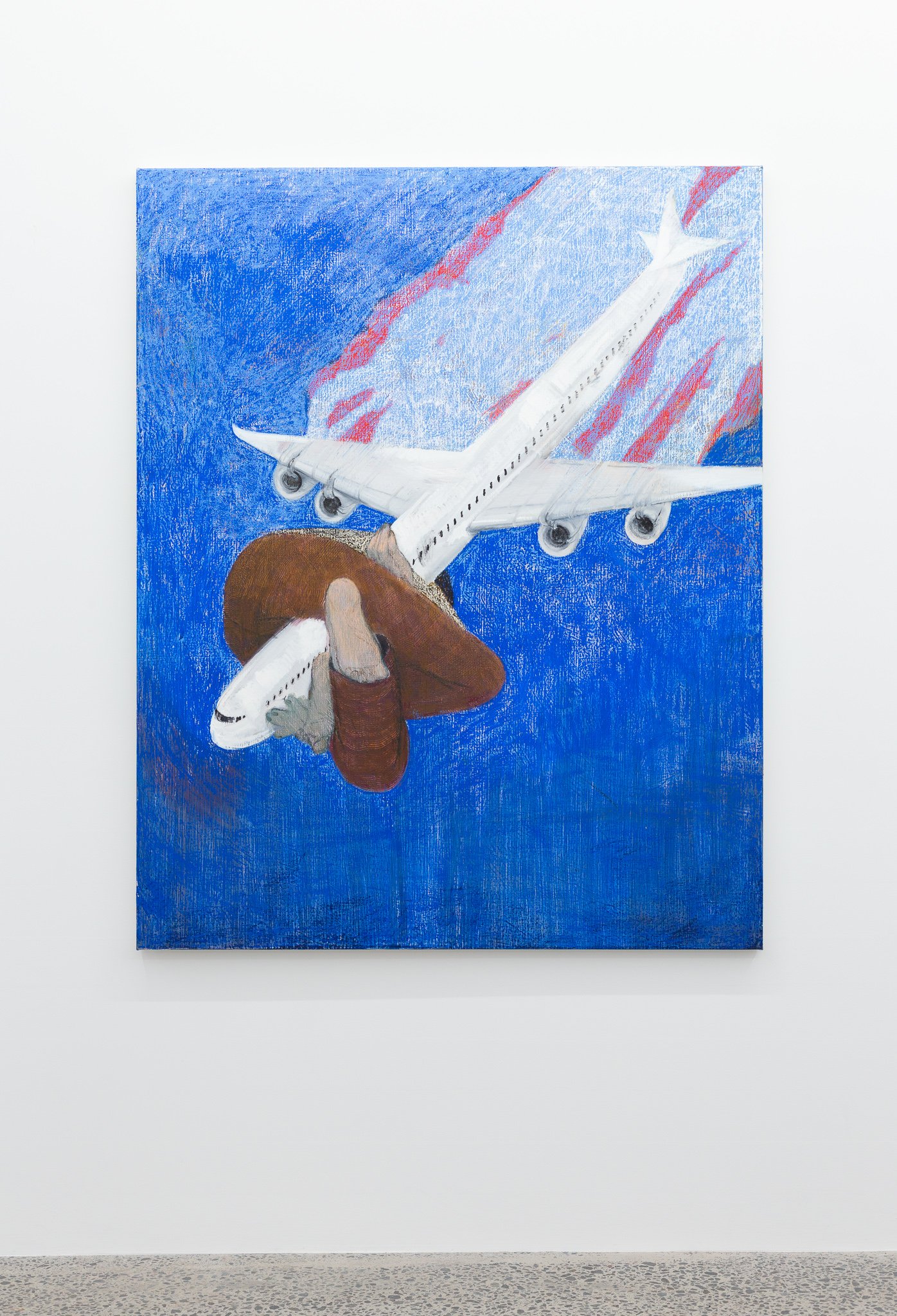

Henry Curchod, Feigning Indifference (detail), 2021, oil stick on linen, 152.5 x 122.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

The crudeness is accidental. I love things that people are uncomfortable talking about, not to be provocative, but because it’s something that pictures can do better than words. Memes do that really well too but in a format that is more direct, transient, intangible, or irreverent. Approaching uncomfortable themes with humour is great, so long as the final image isn’t inherently funny. Then I think you’ve gone too far.

The figures in the works are not supposed to be anyone in particular, in the sense that they are not real people. Kind of deities that represent the collective human, never overtly masculine or feminine, though sometimes the use of gender is important for the narrative. But I don’t want them to be rendered well necessarily or overly defined, just present. I really am not interested in trying to trap people in my paintings, which I think happens a lot. Like if you paint someone you know, you’ve trapped them in your perspective and through your own ability to paint, which might be horrible. They are stuck there forever—misinterpreted and malformed through a relatively clumsy execution. We’ve got things that entrap people really well, like photographs and films and 3D printing. I want to imprison less tangible things, give things that cannot exist a material form.

Henry Curchod, Feigning Indifference, 2021, oil stick on linen, 152.5 x 122.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

To say that Feigning Indifference sits uncomfortably is putting it mildly. A wrestler’s giant body wraps itself around a plane’s fuselage as it plummets to earth, flames and smoke billowing from all four of its engines. There also is a smuttiness to the work, the fuselage absurdly elongated: a distended phallus, that is clear enough for anyone to see. It’s a strange painting. The work seems prescient, disarmingly so.

When the exhibition’s closing date happened, by pure coincidence, to fall on the twentieth anniversary of 9/11, I didn’t feel like it would be particularly wise or fair to have lead the show with that image as it could have been construed as schadenfreude, rather than some awkwards coincidence. And then we saw the heart-breaking images from two days ago at Kabul Airport. Your very strange and ridiculous image resonates loudly—like an enormous brass bell.

Hah! I like that you find it smutty. I have been painting and drawing planes forever. My family situation was relatively odd, so I was constantly alone on planes from about age five, always drawing the planes as they sat in terminals. And then 9/11 happened and I remember everything becoming more tense, and my father started spending many hours in interview rooms in US airports even though he’d done nothing wrong. That confused me. Anyway, I’ve been obsessed with planes and airports from such an early age. Planes are these massive machines that we have to resign our fate to, hoping that they will quickly deliver us to different places in one piece. They are the pinnacle of our ability to move physically long distances with ease, and are strong symbols for so many things (the phallic symbolism was entirely accidental but I needed to make the fuselage long enough to have the figure only wrap around the front of the plane, so that it felt front heavy and headed downwards).

Planes are so special to me, I will fit one in anywhere that I can. But in this painting, I wanted to make an image where the figure was powerful yet helpless—the guy is alone, larger than the plane, has the plane in a headlock and taking it down, and being taken down by the plane . Like that old fable where the frog carries the scorpion across the river but the scorpion stings the frog and sinks them both, because that’s life. In this painting the sky is deep blue and vast, so dense yet without anything to hold onto, nothing to save you—equal parts hope and despair. It’s not supposed to be sad as much as it is supposed to be naturally disorienting.

They are not political images, but they do touch on fundamental human characteristics that historically influence politics: rivalry, ambition, triviality, community, greed, hierarchy, desperation… I could go on. I’d say most of the images touch on those things somewhere, albeit very subtly. In painting I refuse to take a side, sitting idly on the fence because conviction can be so brash.

Henry Curchod, It's always in the last place you look, 2021, oil, acrylic and oil stick on canvas, 152 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

I mentioned the geo-political situation at the start of the interview, because I know from our past interactions, and from your work, that these things do have weight to you, as they do me. Therefore, I find it interesting that you say that they are “not political images.” One of the things that I find most compelling about your work, whilst far from didactic, they nevertheless seem decidedly political. Not always but often. Perhaps it is most apparent because of your heritage—as Iranian (Kurdish), and also Anglo-American? Perhaps it’s inescapable—the politics in your work—simply because of who you are, your apparent otherness.

I take the position that all art is political. Of course, certain works are more actively so, and thus in such cases the politics are more apparent. I would also say that these are also the pieces that have the greatest resonance—the images that stay with us. But if a work is political but not didactic what then?

Maybe they are political. It’s important to note, however, that there are no flags or insignia in the paintings—no nationality, no team. I would hate for them to be read as singular in meaning, to have an overt bias. I have little desire to speak only to my own personal experience—my ethnicity, gender or faith. I want to evoke the feeling of the broader human experience, something that we’ve all felt one way or another. Is it possible to use imagery that seems politically loaded without having a polemic? Possibly, I don’t know. I would say this, I’ve never been fond of art-as-activism. It seems at odds with the way that art communicates; it also seems an exercise equally indulgent and futile.

I use images that I feel have gravity, evoke strong feelings—fear and grief, as well as love and joy. You cannot do this without creating or referencing images that have a certain ubiquity; images that we all know and understand.

This being said, I am quite aware that my heritage colours the work I make. I have never felt a sense of belonging anywhere and I have definitely always felt confused and alienated. I can see one side of my family is very Iranian, and very hurt by history; the other side of my family is very European, carrying their own baggage in other ways. And I am stuck in the middle of these opposing histories and that have always been hard to reconcile (impossible perhaps). And yet, I feel I don’t relate to the histories of my family, I just relate to the effect their experiences had on them as humans.

My grandfather was an advisor to the Shah, a very liberal man who narrowly escaped death by fleeing with his family during the Iranian Revolution in ‘79. I also remember that my grandfather voted for George Bush. This stuff shaped my father, who is somewhat culturally-twisted too. So yes, politics have a presence in my work, but the specifics are hazy, opaque.

What seems most poignant to me is this: that it is quite likely that one day, regardless of where you are from, someone or something bigger and stronger than you will make you run, jump or hide; in fear for your life. Humans have been doing this for as long as we know, and are unlikely to stop anytime soon.

Henry Curchod, Sharing the Sky. Installation view, Sumer, Tauranga, August 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

I can see that through your work there is a desire to reflect upon your place within a complex world. The other day when we spoke, you mused on whether, as an artist, having a preoccupation with paradox was a sign of limited intelligence; that such a consideration was somewhat facile? When you initially said this I thought you were being harsh and self-deprecating but I know now what you mean. To focus solely on paradox also seems to forgo the importance of mystery and storytelling.

I was wondering if you could talk about your work in relation to contemporary painting more broadly. Figuration presently dominates. Often this manifests as a mashup of Surrealism, Genre Painting, Art Nouveau, Post-impressionism…and in your case, also Persian and Islamic Art, Japanese woodcut, Western Desert Art, the list goes on.

If public museum programming and current art market trends are anything to go by, we find ourselves collectively gravitating to work that embodies a clearly-defined politicised (and embodied) subject; and moreover, a subject that is often framed by its otherness. Most often we see this defined as the artists’ difference: be it their ethnicity, indigeneity, sexuality/gender, or neurology (but, weirdly, seldom class—something that I think we are quite blind to in the present moment, culturally speaking). And while there is little doubt that, at a certain level, this hinges on an uncritical romanticisation of The Other—nothing new—and also a desire to atone and undo past wrongs, our colonial legacies; I think to surmise this as its sole reason does not give the whole picture.

There is no doubt that animators behind cartoon programmes are responsible for this whole neo-mystic figuration thing; they were acutely aware of art history, of modernist masterpieces, and extracted different successful elements for use in storytelling for mass broadcast.

Henry Curchod, Irreverent Fucker, 2021, oil and oil stick on linen, 76 x 62.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

A lot of painters working today might use figuration as a means for justifying a set of forms or way of making. Perhaps they are compelled to create something with a specific formal dynamic, but feel the need to create a narrative around it to make it seemingly legitimate. I’ve noticed people all over the world are painting humans as very dangly loose, highly rendered, almost plastic cartoons, so it's not hard to see the influence that animation has had. But maybe telling your particular story becomes the only way to set yourself apart from the ocean of artists doing the exact same thing. And right now the themes with traction are sexuality and ethnicity. These are broad issues that, whilst rooted in Otherness, are palatable and relatable to audiences. Still ‘exotic’, but not affronting. Now there is an ocean of canvases with densely rendered distorted cartoons enduring varying degrees of pleasure and persecution to choose from.

I would also argue that a massive shift happened when Peter Doig became more institutionally (and commercially) accepted. He proved that you could paint fantastical images of mysterious figures in foreign landscapes and be looked at by curators, not just collectors. This was all the encouragement that a generation of art students required. It now seemed possible for one to achieve a form of success whilst making what were ostensibly traditional paintings. So now everyone is doing it and it’s easy for the market to digest. And there’s the internet, which has made everybody’s work so accessible and visible that it is easier to understand your place within a larger trend.

The other factor is that abstraction is scary. You either have to be incredibly brilliant and brave, or dumb and thoughtless to make an abstract painting today. So far, I can’t make an abstract painting because a tense narrative is the only thing I am personally compelled enough by—to make me get up, buy expensive canvas and supplies; and go on a journey to manifest something magical, or possibly shit. I have equal amounts of bewilderment and respect for abstract painters. Us figurative painters are somewhere in the middle, lulled by the safety of representing things that an audience will have a predisposition too, but unable to venture into purer or more conceptual territories. So in order to get our kicks, we abstract the figure. But there are only so many ways you can abstract the figure before it's clear that everything is saturated. Like everything in this day and age, the only thing that stands out anymore is the obscure.

But in response to your question, nothing feels totally new at the moment. Everything derives from something, or several things, that came before it. Now it feels like originality is just an original combination of things, not an original thing in itself. My practice is informed by several conflicting cultures, a relatively odd life, and about twenty other artists that both directly and indirectly showed me how to paint.

“Maybe [my artworks] are political. It’s important to note, however, that there are no flags or insignia in the paintings—no nationality, no team. I would hate for them to be read as singular in meaning, to have an overt bias. I have little desire to speak only to my own personal experience—my ethnicity, gender or faith. I want to evoke the feeling of the broader human experience, something that we’ve all felt one way or another. Is it possible to use imagery that seems politically loaded without having a polemic? Possibly, I don’t know. I would say this, I’ve never been fond of art-as-activism. It seems at odds with the way that art communicates; it also seems an exercise equally indulgent and futile.”

— Henry Curchod

As you say, the internet has greatly expanded our knowledge of other artists working across the globe, both current and past. We tend to think that nothing is new these days because our understanding of what constitutes art is both broad and liberal—both as a result of the far reach of imperialism and colonisation, and also more than a century of conceptualism in art. Nevertheless radical shifts do take place. Often they coincide with larger societal shifts. Maybe we are on another such threshold? (Then again we always think this. It seems part of our secular collective psyche—our doomsday imaginings, our hysteria and inability to speak of death… I digress.) Another thing to bear in mind is that radical actions are not always given their dues at the time and their significance is only acknowledged in hindsight. We have a strange concept of history as if it were static. It isn’t. It's only that history moves so slowly that we don’t even notice its change. Art history—the canon—is no different. We only have to look at the given importance of Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Clark, Charlotte Posenenske, and more recently, and more relevant to discussions here, Kerry James Marshall and Hilma af Klimt. The canon, like history more broadly, is constantly being rewritten.

I realised that as soon as I described a mashup of Genre Painting and Post-impressionism that all roads would seemingly lead to Doig. But he is just one artist and only tells part of the story. Right now you have artists like Michael Armitage, whose work certainly owes a lot to Doig but seems to be doing something altogether different. If we think of Genre Painting one can’t underestimate the work of Marshall, his importance to Armitage’s work and a whole generation of artists, black or otherwise; and speaking more locally I would (of course) say the same about your work and that of Juan Davila.

I find it interesting that while a large array of painting styles are seeing a resurgence in contemporary practice—often with roots in early to mid-twentieth century Europe (Synthetic Cubism, Expressionism, Fauvism, etcetera)—what is most startling, like in your work, is this fusion of Genre Painting combined with Surrealism. Artworks that have one foot in the quotidian, daily reality, and the other in a deeply psychological, internal space. Sludgy, weird and unstable. Also mystical. What can we make of this?

Why painting? It’s accessible and ‘valuable.’ Why the surreal? Well, if everything pre-existing in the world feels decently represented, then that leaves the psychological internal space as very exciting territory.

Surreal Genre Painting, or painting scenes from daily life with added mystical or spiritual elements, is a vital limb of the tradition of painting, it is not a new thing at all. It has been common amongst many cultures (particularly eastern cultures) for hundreds of years. I would even argue that Hieronymus Bosch was a Surreal Genre Painter. But it's so popular right now that the western canon is going to need a name for it.

You can make videos, NFTs, alternate digital realities, massive immersive installations, and it’s all helping build a picture, but painting still feels like the most accessible way to explore this internal space. I’d argue that digital 3D modelling (or even Elon Musk’s Neuralink) may offer more in the future, but at the moment those tools are far too resource-heavy to be deemed a feasible way of expressing yourself with the same freedom that a drawing or painting can. It also lacks a human quality that people seem to value when trying to relate to an image.

Artistic movements and trends are historically informed by technological advancements, so it’s easy to see that with so many different avenues to explore, one would assume that in order to be deemed progressive we must be working in augmented reality. But I would say that the potential of technology to inform art grew so fast that it may have broken this historic correlation. And so many artists have receded back into the cave to see what was left behind. At least for the moment. The only format I really see to be much of an adversary to drawing and painting is memes. But it's still early days.

From my perspective, the goal is still to describe the human experience, and there’s so many ways to do that now. We are still mystical, spiritual beings, and the need for exploring that still exists, no matter the form. And maybe painting semi-abstract figures in surreal spaces is the cleanest way to reach that right now. There is an obvious yearning for another world, a need to escape in these paintings at the moment. It seems like an appropriate reaction to a world that is more confusing than ever. Seriousness is somehow more painful right now, so we are telling the story of a generation who want out, in order to find a way in.

Together, the collective fantasies and perspectives of thousands of contemporary artists working across different media, covering many different ideas, is ultimately building a very thorough picture of our shared experience. Each one is playing a crucial part in describing a radical existence, from the mundane to the profound.

And yes everyone has been helpful in building this language, from Bosch and Edvard Munch to Marshall. I also love the work of John Baldessari and Joseph Kosuth. I don’t believe they were singing my song, but they definitely illuminated some of the boundaries.

I think drawing and painting is the most magical, beautiful, and universal language we have and I don’t blame anyone for wanting to do it all the time, and trying their best to carve something from it.

Henry Curchod, Deglazing, 2021, oil and oil stick on linen, 112 x 168.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

Henry Curchod, The tadpole that lives in every pond, 2021, oil and oil stick on linen, 150.5 x 122.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

Henry Curchod, Irreverent Fucker, 2021, oil and oil stick on linen, 76 x 64.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

Henry Curchod, Plunge, 2021, oil and oil stick on linen, 152.5 x 258.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

Henry Curchod, Plunge (detail), 2021, oil and oil stick on linen, 152.5 x 258.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

Henry Curchod, Sharing the Sky. Installation view, Sumer, Tauranga, August 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

Henry Curchod, Sharing the Sky, Sumer, Tauranga, 11 August–11 September 2021

Gallerist Dan du Bern of Sumer on Hikalu Clarke’s current exhibition at the gallery.